33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave #28 Korean Food Ecstasy

33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave

#28 Korean Food Ecstasy

*한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드 #28 한식 엑스타시 <Korean version>

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/?mid=Focus&document_srl=4088481

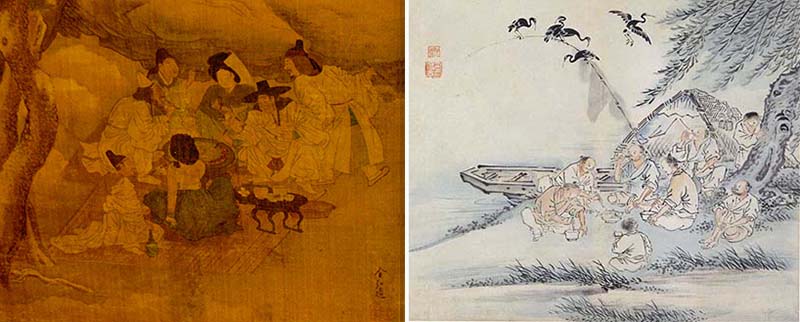

Kim Hong-do (1745-1806), Travel Genre Paintings - Seolhooyayeon (detail), light coloring on silk, 1778, Collection of Musée Guimet, Paris Photo: Sukie Park/NYCultureBeat / Kim Deuk-sin (1754-1822), Gangsanghoeum, light coloring on paper, Gansong Art and Culture Foundation collection

In Kim Hong-do’s 8-panel Travel Genre Paintings (*see bottom of article for full photo), which I observed at the Musée Guimet, an Asian art museum, during a trip to Paris in 2016, “Seolhooyayeon” was particularly captivating. This work depicts scholars sitting with courtesans on a mat under a pine tree on a snowy winter night, illuminated by the full moon, grilling meat, and drinking together.

“Gangsanghoeum” by Kim Deuk-sin, considered one of the three greatest genre painters of Joseon alongside Kim Hong-do and Shin Yun-bok, depicts fishermen anchoring a boat under a willow tree on a summer riverside and then sitting around eating a fish. Four water birds are looking down at their meal from the air.

The atmosphere of scholars enjoying the taste of bulgogi and alcohol in the cold winter mountains in “Seolhooyayeon” and the fishermen sharing rice with a single fish on the riverside in “Gangsanghoeum” depict Koreans in the Joseon period enjoying picnics and being natural gourmets.

Koreans’ passion for food is unparalleled. There’s a saying that you should eat even before sightseeing at Diamond Mountain (Mt. Geumgang). Regardless of their financial circumstances, Koreans prepare an abundance of food to the extent that the legs of the table may break when guests visit their homes. Koreans are people who cannot give up rice and kimchi, no matter which country in the world they go to and put down roots in, people who made Mukbang popular worldwide, countries with local foods all over the Korean Peninsula, and wisdom that developed unique food for each of the four seasons. Koreans are an ethnic group whose hobby is gluttony.

Today, Korean food is captivating the taste buds of people around the world. Korean American chefs David Chang, Corey Lee, Edward Lee, Danny Bowien, Hooni Kim, Roy Choi, and Jeonghyun Park are currently serving food in the North, South, East, and West of the United States. The reason Koreans lead the food culture is probably that they possess a special DNA for Korean taste. The spectrum of Koreans’ tastes seems unrivaled.

#Andy Warhol and Mukbang

Andy Warhol eating a hamburger <YouTube> / The Food Porn Superstars of South Korea: Mukbang <YouTube>

American pop artist Andy Warhol filmed the documentary “Eat” (39 minutes. 30 seconds) in black and white in 1963, featuring fellow artist Robert Indiana eating mushrooms. In 1981, Warhol created a video titled “Andy Warhol eating a hamburger” (4 minutes, 27 seconds), showcasing him enjoying a hamburger. In front of the camera, he takes a hamburger from a paper bag, adds ketchup, eats it, and then sits quietly for a while. The video concludes with the statement, “Hello, my name is Andy Warhol, and I just finished eating a burger,” followed by the subtitle -Burger, New York-.

Today, Koreans have turned 'eating' into a global phenomenon through a performance known as Mukbang (eating broadcast/eatcast), which originated on the internet broadcasting service AfreecaTV in 2010. Mukbang YouTubers go beyond simply eating mushrooms or hamburgers; they prepare lavish meals and savor their food. There’s a poignant aspect to the sight of solitary individuals, both young men and women, relishing a feast alone.

Since then, numerous TV programs with the Mukbang concept have emerged in Korea, including “Solitary Gourmet,” “Please Take Care of the Refrigerator,” “Delicious Guys,” “Bob (Rice) Bless You,” “Wednesday Food Talk,” “Street Food Fighter,” “KPopStar Eats,” “Gourmet Road, Stars’ Top Recipe at Fun-Staurant,” “What Shall We Eat Today?,” “We Will Eat Well,” “Girls Who Eat Well,” “Quiet Dining,” “Queen of Home Cooking,” “Tasty Road,” “Let’s Eat Dinner Together,” and more. This trend has also gained popularity worldwide on YouTube, giving rise to Mukbang stars and millionaires.

#Anthony Bourdain and Choi Bool-am

President Barack Obama and Anthony Bourdain in “Parts Unknown” Hanoi (2016) / Choi Bool-am in “Korean Cuisine and Dining” Ssambap (2013)

Until a few years ago, the most popular food and travel programs in the United States were CNN’s “Parts Unknown” (2013-18)' hosted by the late Anthony Bourdain (1956-2018), and the Travel Channel’s “No Reservations” (2005-12). Anthony Bourdain, a former chef, transcended the limited food culture of the United States, embarking on a global journey in search of the tastes of the global village. With his sharp taste and intelligence, he demonstrated that “the world is wide, and there is a lot of food.”

Bourdain, enjoying $6 Bun Cha (charcoal pork rice noodles) and Hanoi beer with President Barack Obama in the Hanoi, Vietnam episode of “Parts Unknown” in 2016, also went to a restaurant with director Wong Kar-wai’s cinematographer Christopher Doyle in the Hong Kong episode. Bourdain, who particularly loved Korean Army Stew, passed away suddenly in 2018, leading to the discontinuation of the program.

Meanwhile, in Korea, “Korean Cuisine and Dining” on KBS-TV has been exploring flavors from all over the country since 2011. This food documentary features veteran actor Choi Bool-am from MBC-TV’s “Chief Inspector” and “Country Diaries” introducing local food, history, and stories of people across the country. As of March 28, 2024, Mr. Choi Bool-am’s savory and straightforward commentary has spanned 649 episodes. He has explored rich history and wisdom, featuring destinations like Heuksando skate, Seosan seaside village table, Busan refugee table, Jeju Island noodle road, and DMZ road, all developed during times of poverty. “Korean Cuisine and Dining” delves into the culinary roots of the Korean people, showcasing not only local foods from around the country but also the history of the regions and the life stories of the people.

#All in One, Korean Dining Table

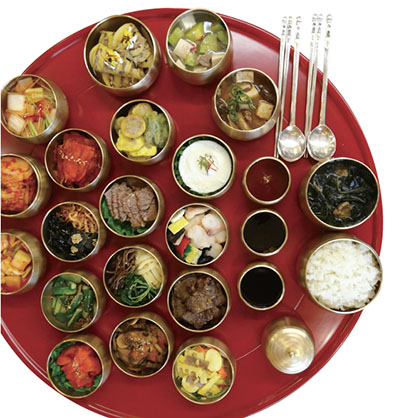

Surasang, reproduced based on the testimony of Han Hee-soon (1st artisan holder, 1889-1971), the last court lady of the Joseon Dynasty.

Korea, a small country nestled between China and Japan in the Far East, boasts a rich food culture and an array of sophisticated recipes. Depending on the number of side dishes on the table, ranging from 3-cheop to 5-cheop, 7-cheop, 9-cheop, and even the grand 12-cheop King’s surasang, hosts must prepare so many dishes and side dishes when guests come that the table’s legs threaten to break. It is truly unrivaled.

In contrast to the Western multi-course meals, Korean cuisine’s “all in one” style table setting, which includes soup, rice, kimchi, and side dishes, embodies openness, efficiency, autonomy, balance, and harmony. At a glance, you can see all the food, choose according to your taste, and eat at your own pace. In other words, the table is set with consideration for the eater. Koreans are a “quick, quick” people, who excel at speed warfare.

On the other hand, the Western appetizer-main dish-dessert style course meal appears more centered on the part of the chef preparing it than the person eating it. Unless the day’s meal menu is revealed in advance, eaters must simply consume what is given and wait until the next course is served. This is an elegant but very slow-paced meal.

When it comes to Korean food, the person eating it even has the ability to cook it, too. In a Korean restaurant, it is natural for customers to grill meat and boil hotpot at the table. People from other ethnic groups who are not familiar with this culture are now learning and enjoying Korean table barbecue, where they cook and eat themselves. Korea’s unique food culture, which reduces kitchen labor and allows customers to participate in the process, is spreading.

# The Language of Taste: How Koreans Describe Flavor

Korean dining is an immersive, multi-sensory experience. We see the vibrant colors, inhale the bold aromas, hear the sizzle of bulgogi or the bubbling of hotpot, savor the complex layers of flavor, and feel the fiery heat of spices coursing through our bodies.

After eating, we often describe the sensation as feeling “refreshed” or “cooled down,” much like stepping out of a sauna. For Koreans, food is not just about taste—it is a holistic experience that excites both body and soul. This thrilling, full-body “food ecstasy” is unparalleled, a primal joy that few other cuisines can replicate.

Korean cuisine is not just about eating—it’s about experiencing a spectrum of tastes, textures, and sensations. The Korean language reflects this deep culinary awareness, with over 400 words dedicated to describing flavors, mouthfeel, and cooking techniques.

While many cultures recognize the five basic tastes—sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami—Korean cuisine extends beyond this spectrum, adding the nuance of spiciness in multiple variations. At a soft tofu stew (sundubu jjigae) restaurant, spice levels might be categorized as: “not spicy” (an maepge), “mild” (yakage), “medium” (botong), “spicy” (maepge), and “extra spicy” (aju maepge). For those who enjoy Korean instant noodles, spice levels range from the classic buldak ramen to the infamous “nuclear” (haek buldak) ramen, pushing the limits of heat tolerance.

Untranslatable Korean Flavor Words

Korean offers unique vocabulary to describe flavors that are difficult to translate into English:

- Savory and Nutty: Gusuhada (구수하다): A rich, roasted taste found in toasted barley tea or perilla seeds.

- Mildly Salty Yet Refreshing: Sumsumhada (슴슴하다): A balanced, gentle saltiness that’s neither overpowering nor bland.

- Tangy & Slightly Bitter: Ssapsaeraehada (쌉싸래하다): A pleasant bitterness, often used for herbal teas or medicinal plants.

- A Comforting Aftertaste: Gaewoonhada (개운하다): A light, clean taste that refreshes the palate, like a sip of warm soup.

Even spiciness has many variations:

- Eolkeunhada (얼큰하다): A warm, comforting heat, like spicy Korean stews.

- Kalkalhada (칼칼하다): A sharp, refreshing heat, often found in kimchi jjigae.

- Maekomhada (매콤하다): A pleasant, mild spiciness, like spicy stir-fried pork (jeyuk bokkeum).

Korean also distinguishes food by texture, with words like:

- Tangeul-tangeul (탱글탱글): Springy and chewy, like freshly made rice cakes (tteok).

- Jjonddeuk-jjonddeuk (쫀득쫀득): Sticky yet firm, like mochi or glutinous rice cake.

- Gudeok-gudeok (꾸덕꾸덕): Dried and slightly firm, used for semi-dried pollock (bugeo).

A Reflection of Culinary Expertise

Beyond taste and texture, Korean culinary vocabulary extends to cooking techniques. The way an ingredient is sliced can vary widely, with terms like: diagonal cutting (eoseut sseolgi), mincing (jjongjjong sseolgi), and julienne slicing (chaeseolgi).

Even methods of preparation showcase Korea’s deep connection between language and cuisine: slow simmering (orae dari-gi), thick reduction (jindeukhage jori-gi), and tossing with seasoning (beomurigi) all reflect the precision of Korean cooking.

This rich linguistic landscape highlights how Korean food is not just about flavors but about precision, tradition, and the sensory experience of eating.

#Korean Slow Food: The Flavor of Time

Kisan Kim Chun-gun, Making Yeot (Korean taffy), late 19th century, Museum of Ethnology, Vienna / Making Rice Cake, late 19th century, Museum of Ethnology, Vienna / Making Tofu, late 19th century, Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg

American anthropologist Margaret Mead once noted in the American Anthropological Journal that Koreans, alongside the Bodi tribe of East Africa, are remarkable for their meticulous methods of preparing beef. While the French and English recognize 35 cuts of beef and the Bodi tribe identifies 51, Koreans distinguish an astonishing 120 parts—a testament to their extraordinary attention to detail and resourceful approach to food.

Korean history has been marked by hardship. As historian Yoo Bong-young noted in a 1970 paper, Korea has experienced over 931 conflicts throughout its history. Despite these challenges—including Japanese colonization and the devastating Korean War—Koreans have cultivated a rich and diverse food culture. Unlike China, which emphasizes stir-frying due to its vast population and geography, or Japan, known for raw fish, Korean cuisine is distinguished by its fiery flavors and diverse cooking techniques. From blanching, steaming, and simmering to grilling and fermenting, Koreans have developed culinary methods that maximize every resource.

In times of scarcity, Koreans demonstrated remarkable ingenuity, creating soups and stews from the smallest pieces of meat and finding uses for every part of the animal. Iconic staples staples like dotorimuk (acorn jelly), ganjang gejang (soy sauce crabs), sannakji (live octopus), kkaennip (perilla leaves), and kongnamul (bean sprouts), all of which reflect a deep respect for resourcefulness and balance in food.

Koreans have long embraced a resourceful approach to food, ensuring that no ingredient goes to waste. We add rice to soup (gukbap), mix it with vegetables and meat (bibimbap), or fry it with leftovers (bokeumbap). Even small scraps of meat and vegetables are boiled into stew (jjigae), creating a rich and flavorful dish from what remains.

Few countries rely on fermentation as much as Korea, where staples like ganjang (soy sauce), doenjang (soybean paste), gochujang (red chili paste), kimchi, and jeotgal (salted seafood) form the backbone of its cuisine. Various vegetables are pickled to make kimchi, while seafood is transformed into jeotgal, ensuring that fresh ingredients can be preserved and enjoyed year-round. These slow-aged, deeply flavored foods reflect Korea’s commitment to slow food, where time and patience enhance both flavor and health."

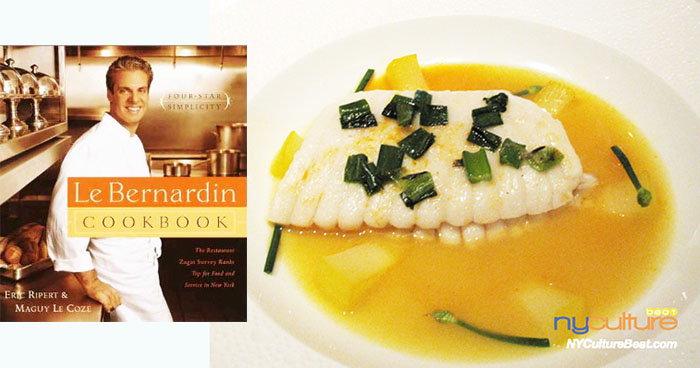

Chef Eric Ripert’s “Le Bernardin Cookbook”/ Poached Skate; Braised Daikon, Charred Scallion Jam/ Lemon Confit-Kimchi Broth at Le Bernardin, Michelin 3-Star New York restaurant

In the United States, fish like skate and monkfish were until recently overlooked. Koreans, on the other hand, have a history of savoring the distinct flavor (ammonia) of skate through various preparations, including skate sashimi, steamed skate, skate pancakes, fried skate, spicy raw skate salad, and skate served with boiled pork and aged kimchi. Presently, domestically produced skate from Korea is pricey and primarily available in high-end Korean restaurants or hotels, with most of it being imported from countries such as Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.

Monkfish, often considered an unattractive fish, earned the moniker “poor man’s lobster” in the United States due to its affordability and similar taste profile. In Korea, monkfish remained prevalent, as the Japanese depleted fishing reserves in the South Sea during the colonial period. The discarded monkfish found new life in dishes like steamed monkfish with bean sprouts, red pepper powder, and other seasonings.

In recent times, American chefs have recognized the allure of skate and monkfish—both economical and delicious—and frequently feature them on the menu, including at Le Bernardin, a Michelin 3-star restaurant in New York. These dishes also take center stage in the New York Restaurant Week set menu, because of their relative affordability.

In Korea, a diverse cuisine has evolved with unique recipes for each region, extending beyond skate and monkfish. For ribs alone, variations include beef ribs (Pocheon, Suwon, Pyungchang, Gwangyang, Andong, Geochang), pork ribs (Incheon, Damyang), charcoal-grilled ribs (Mapo), tteokgalbi (Gwangju), and steamed ribs (Daegu). Soups display regional diversity with options such as bean sprout soup (Jeonju), beef head soup (Gwangju), Ttaro Gukbap (Daegu), *Olgaengi Gukbap (marsh snail, Cheongju), and *Sugure Gukbap (*the gluey area between cow skin and beef, Changnyeong), each enjoyed with unique regional recipes.

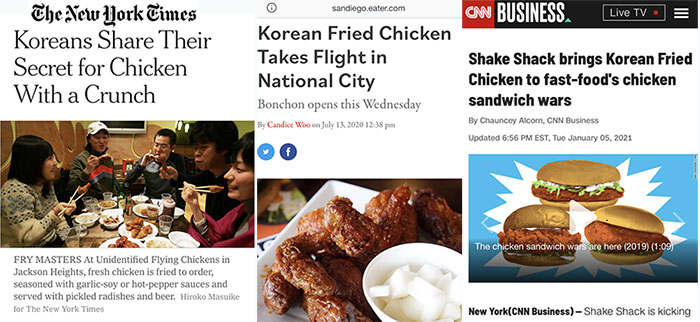

#Korean Fried Chicken (KFC?) Craze

Korea is also a “Chicken Republic,” where fried chicken holds a special place in the hearts of its people. As of 2019, there are approximately 87,000 fried chicken restaurants in Korea—more than twice the number of McDonald’s restaurants worldwide (38,000 as of 2020). Korean chicken establishments have achieved global recognition through intense competition and innovative recipe development.

After the worldwide popularity of bulgogi, bibimbap, and kimchi, Korean fried chicken has also become a global sensation. Varieties such as sweet and salty soy sauce-garlic seasoned chicken and sweet and spicy red pepper paste-seasoned chicken, representing seasoned fried chicken with Korean soy sauce, have delighted taste buds globally. The low-fat content and crispy texture have played a significant role in this international acclaim.

In 2006, fried chicken chains like Bon Chon Chicken, Kyochon Chicken, and Cheogajip (Mother-in-law’s House) opened branches in quick succession in New York and New Jersey, igniting a Korean chicken craze.

Meanwhile, the American burger chain Shake Shack introduced its “Korean-Style Fried Chick’n” series in 2021, featuring gochujang-glazed crispy chicken breast topped with toasted sesame seeds and gochujang fries, served with white kimchi slaw.

While it might be tempting to think of fried chicken as an import to Korea from the United States, historical records suggest otherwise. In the Joseon Dynasty cookbook “Sangayorok” (山家要錄, 1450s), there is a recipe for “pogye” (fried chicken): “Cut a fat chicken into 24-25 pieces, heat the oil in a pot, place the meat in it, and quickly turn it over. Then, mix soy sauce and sesame oil with flour, cook it, and serve it with vinegar.” However, given the scarcity of oil and flour during that period, it is presumed to have been a dish served by powerful aristocrats to their esteemed guests.

#New York K-Food Pioneer - Hangawi

Hangawi Restaurant, NYC

Long before the Korean Wave, which includes K-Pop, K-Drama, K-Movie, and K-Beauty, the K-Food (Korean Food Wave) quietly started on 32nd Street in Manhattan. On Christmas Eve 1994, at a time when “Korean food” in the United States was synonymous with kimchi, bulgogi, bibimbap, and japchae, restaurant “Hangawi” opened its doors just a block away from K-Town (32nd Street, between 5th-6th Avenues), the hub of Korean restaurants.

Upon opening the main door, decorated like a substantial Korean traditional house, and stepping inside, the space is adorned with patchwork cloths, Korean paintings, and traditional teacups, while soft Korean traditional music plays in the background. As you remove your shoes, settle on the floor, and sit on a cushion, a server dressed in hanbok and bosun (socks) welcomes you with fluent English and polite manners. The cutlery in silk pouches elegantly introduces Korean culture. Unlike other Korean restaurants in New York, Hangawi focuses on vegetarian menus, offering items such as pumpkin porridge, grilled deodeok (mountain root-lance asiabell), japchae, and gopdol bibimbap, neatly organized into starter/appetizer/main dish/dessert categories. The restaurant also presents course menus like the “Emperor's Meal.”

Within a month of its opening, Hangawi garnered praise from Ruth Reichl, the restaurant critic for The New York Times, who wrote: “Leaving Hangawi, I felt cleansed and refreshed, as if I had come from a spa instead of a new vegetarian Korean restaurant. This is partly because the experience of eating in that calm, elegant space with its smooth wooden bowls and heavy ceramic cups is so utterly peaceful. And partly because even after a two-hour meal of many courses my body still felt buoyant.”

Ruth Reichl, The New York Times <Jan. 27,1995> -

Reichl’s poetic review served as an invitation to New Yorkers to explore K-Town. Despite its prime location near the Empire State Building, Penn Station, and Macy’s Department Store, Koreatown, filled with Korean restaurants, was somewhat unknown for people from other ethnic groups. Most eateries catered to busy Korean immigrants and tired Korean tourists with “comfort food,” featuring subpar menus, language, and service. In essence, these establishments were created by Koreans, for Koreans, and of Koreans.

Hangawi distinguished itself from other K-restaurants with a vegetarian concept, elevating its menu, interior, and service to welcome not only New Yorkers but also vegetarians from around the world. Hangawi, which is the Korean word for the mid-Autumn festival (or Chuseok), located in the middle of New York, became an “oasis of calm” in Manhattan.

In the Zagat Survey, an annual guide that tabulated reviews of restaurants by New York restaurant-goers often called the “foodie’s bible,” Hangawi consistently ranked high as both a Korean restaurant and a vegetarian restaurant. In 2015, Zagat awarded Hangawi the highest score for a vegetarian restaurant in New York: 26 points (out of 30) (Food)/26 points (Deco)/25 points (Service). http://hangawirestaurant.com

#Korean Temple Food and Monk Jeong Kwan

The Netflix documentary series “Chef’s Table” introduces Monk Jeong Kwan and the world of Korean temple food.

Amidst the rising trends of veganism, vegetarianism, the farm-to-table movement, and wellness-focused dining, Korean temple food has garnered renewed attention. Monk Jeong Kwan from Baekyangsa Temple Cheonjinam (Jangseong, Jeollanam-do) has emerged as a star in the global restaurant industry.

Eric Ripert, chef/co-owner of Le Bernardin, a 3-star Michelin seafood restaurant in New York and a practicing Buddhist, has a profound fascination with Korean temple food. His journey took him to Baekyangsa Temple, where he learned about temple cuisine from Monk Jeong Kwan. Ripert even invited the monk to Le Bernardin for a demonstration. In 2015, he featured Monk Jeong Kwan and temple food in his “Korean Temple Food: Feed the Soul” episode of “Avec Eric,” which aired on the American public TV station PBS.

Ripert introduced Korean temple food to New York Times reporter Jeff Gordinier. Gordinier, captivated by Monk Jeong Kwan’s culinary creations at a tasting event at Le Bernardin, visited Korea. In an October 2015 article titled “Jeong Kwan, the Philosopher Chef,” Monk Jeong Kwan was hailed. Gordinier wrote: “Kwan is an avatar of temple cuisine, which has flowed like an underground river through Korean culture for centuries. Long before Western coinages like ‘slow food,’ ‘farm-to-table’ and ‘locavore,’ generations of unsung masters at spiritual refuges like Chunjinam were creating a cuisine of refinement and beauty out of whatever they could rustle up from the surrounding land.”

René Redzepi, the chef of Copenhagen’s Noma restaurant, also traveled to Korea to learn about temple food. Noma, a Michelin 3-star restaurant, has been ranked #1 in the world’s best restaurants five times (2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2021) by the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

Korean temple cuisine adheres to the “abstinence” recipe, avoiding ingredients like garlic, green onions, chives, wild chives, and leeks, which are not consumed in Buddhism. Monk Chef Jeong Kwan, a practitioner, has described temple food as having a taste that goes beyond the five flavors sensed with the mouth, transcending into the realm of the mind. She expressed it as “the taste of Zen that opens the body and relaxes the mind.”

The story of Monk Jeong Kwan and temple food gained prominence in the 2017 Netflix documentary “Chef’s Table, Season 3,” directed by David Gelb, which was invited to the Culinary Cinema section of the Berlin International Film Festival. Once known as “jeolbap” (temple rice), Korean temple food is now capturing the attention of the global culinary industry.

#Korean restaurants earning Michelin stars

Michelin Guide New York / Chef Corey Lee (Dong-min Lee) of Benu in San Francisco, the first Korean chef to receive three Michelin stars.

Why do many Koreans insist on eating Korean food even when traveling abroad? Our tongue, accustomed to the taste of fermented foods such as kimchi and red pepper paste, knows the unique taste of Korean food, which is so thrilling and satisfying that it sends shivers through the body, in addition to sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. For those of us who know the taste, even Michelin-starred restaurants in the U.S. or Europe are unsatisfying. We are Koreans who cannot live without kimchi and red pepper paste.

Koreans are people who see the food (with their eyes), smell it (at the table), listen to it (bubbling hotpot or sizzling bulgogi), savor it in their mouths, and feel (the spicy taste) with their whole body. We say “I feel refreshed” or “cool” after eating. Korean food stimulates the nerves of your entire body as if you just came out of a sauna. For Koreans, eating is a holistic experience. The cool, refreshing taste and feeling can be called a “food orgasm.” We cannot feel this thrilling excitement, the “food ecstasy” that Korean food gives us, in the food of any country in the world. The desire for Korean food seems to be a primal desire that we cannot give up.

Korean food is now captivating people all over the world and is earning Michelin stars that chefs around the world admire. In 2023, New York saw 11 restaurants by Korean chefs being honored with Michelin stars. Notably, Atomix and Jungsik maintained their 2-star rating, while David Chang's Momofuku Ko, previously holding two stars, was excluded following its closure in November. Among the 1-star Michelin recipients were Cote, Kochi, Jeju Noodle Bar, Jua, Mari, Oiji Mi, Joomak Banjum, Bōm, and Meju. Consequently, out of the 73 Michelin-starred establishments in New York, 11 proudly represent Korean cuisine.

Leading the pack with three stars each were Eleven Madison Park, Le Bernadin, Masa, and Per Se. While several Japanese restaurants, such as the renowned 3-star Michelin Masa, and various sushi establishments received stars, none of the Chinese restaurants in New York were similarly recognized.

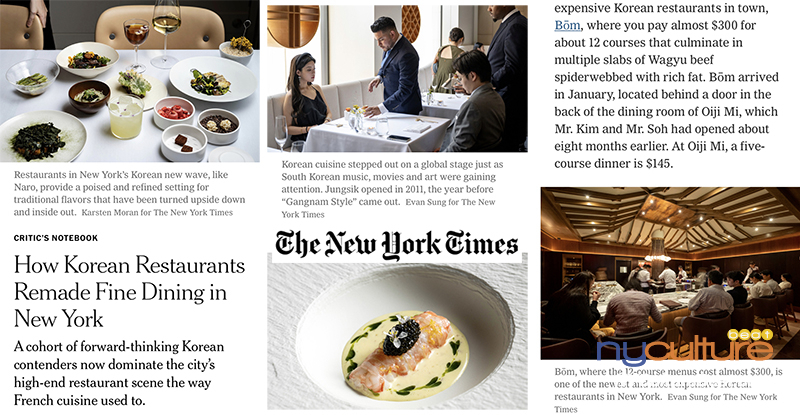

In August 2023, New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells penned an article titled “How Korean Restaurants Remade Fine Dining in New York,” noting a significant shift in the city's culinary landscape. Wells remarked, “the flavor of fine dining has changed a lot lately. Korean owners and chefs now run about a dozen of the city’s most prominent high-end restaurants. Their rise, which has been remarkably swift, brings to an end the unquestioned supremacy of French cuisine that lasted for decades.”

Highlighting New York's evolving gastronomic scene, Wells emphasized, "No American city can beat Los Angeles for traditional Korean food. But New York almost certainly has a more varied and exciting group of restaurants where the cuisine is regularly turned upside down and inside out. Outside South Korea, Manhattan is the best place to experience alternate visions of Korean cuisine, to taste classic flavors run through the dual prisms of technique and imagination."

In the article, he highlighted the adeptness of Korean chefs in impressing the Michelin guide. In the most recent New York edition, nine modern Korean restaurants were awarded stars, showcasing their culinary excellence. In stark contrast, no stars were bestowed upon Chinese restaurants, despite their resurgence in New York fueled by significant investment from China and an increasing population of affluent Chinese residents eager to indulge in upscale dining experiences. While high-end Japanese restaurants outnumber Korean establishments in the city, with potentially more omakase sushi counters alone, the influence wielded by Korean chefs transcends mere numerical comparison. Their impact on the dining scene surpasses their representation in sheer numbers, underscoring the profound impression Korean cuisine has made on New York's culinary landscape.

*Beyond BBQ and Kimchi: Five Korean-American Star Chefs at Inside Korea’s Table

Mainstream food companies in the U.S. are now embracing the flavors of Korean cuisine. In April 2024, Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) introduced a Korean BBQ sauce for their chicken nuggets, and in July, Hormel Foods launched SPAM with Korean BBQ flavor. <update>

Sukie Park

A native Korean, Sukie Park studied journalism and film & theater in Seoul. She worked as a reporter with several Korean pop, cinema, photography and video magazines, as a writer at Korean radio (KBS-2FM 영화음악실) and television (MBC-TV 출발 비디오 여행) stations, and as a copywriter at a video company(대우 비디오). Since she moved to New York City, Sukie covered culture and travel for The Korea Daily of New York(뉴욕중앙일보) as a journalist. In 2012 she founded www.NYCultureBeat.com, a Korean language website about cultural events, food, wine, shopping, sightseeing, travel and people. She is also the author of the book recently-published in Korea, "한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드: 방탄소년단(BTS), '기생충' 그리고 '오징어 게임'을 넘어서 (33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave: Beyond BTS, Parasite, and Squid Game)."

한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드

*Buy Here <US>

-KBOOKSTORE US $48.60

https://kbookstore.com/catalog/product/view/_ignore_category/1/id/694563/s/33-9788978895323

-반디북스 Bandi Books US $51.30

https://www.bandibookus.com/front/product/detailProduct.do?prodId=4461303

888-880-8622(Toll Free)

-고려서적 Koryo Books $90-$100

맨해튼 212-564-1844/ 뉴저지 201-461-0008

*Buy Here <Korea>

-알라딘 Aladin ₩40,500

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=318150433

[신간 안내] 한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드: 방탄소년단(BTS), 기생충과 오징어 게임을 넘어서

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Lounge2&document_srl=4097797

[NEW Book] '33Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave: Beyond BTS, Parasite and Squid Game'

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Zoom&document_srl=4097451

[언론 보도] 한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드

한국 중앙일보(중앙Sunday), 뉴욕 중앙일보, LA 중앙일보, 밴쿠버 중앙일보, 뉴욕일보, LA한국일보, 라디오 코리아...

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=CulBooks&document_srl=4097741

[Media Coverage] '33Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave: Beyond BTS, Parasite and Squid Game'

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?document_srl=4097755&mid=Lounge2

[서점 통신] 한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드: 출간 이후

교보문고(반포 지점) 비치/ 알라딘 주간 베스트 인문-문화이론 부문 40위(6/13)/ 알라딘 첫 리뷰

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Lounge2&document_srl=4098111

*[들어가는 글] 뉴욕에서 한류를 목격하며...

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?mid=Focus&document_srl=4099765

-Elaine-