33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave, Hallyu #4 People of Resistance

33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave, Hallyu

#4 People of Resistance

From the March 1st Movement to the Candlelight Revolution

*한류를 이해하는 33가지 코드 #4 저항의 문화 <한국어 버전, Korean version>

https://www.nyculturebeat.com/index.php?document_srl=4137185&mid=Focus

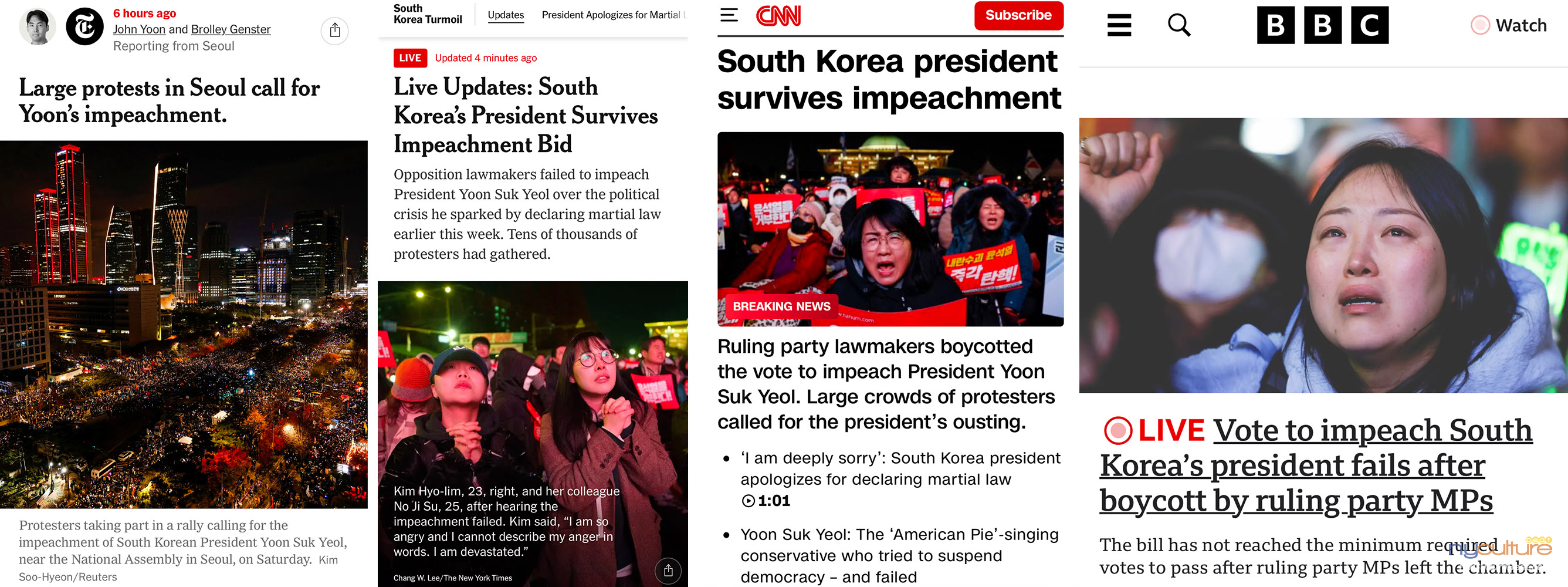

On December 7, 2024, over one million citizens gathered in front of the National Assembly building in Yeouido, Seoul, for the “National Candlelight March: Resign, Sedition-Criminal Yoon Seok-yeol!” The impeachment vote against President Yoon Seok-yeol, who had declared martial law on the night of December 3, was automatically canceled due to a collective boycott by the ruling People Power Party. Major global media outlets, including The New York Times, CNN, and BBC, provided detailed coverage of the protests that day.

From Martial Law to Impeachment: Korea's Non-Violent Revolution

In the fall of 2024, Koreans were filled with excitement. In early October, novelist Han Kang became the first Asian woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, while pianist Yunchan Lim won Gramophone's Classical Music Award, Young Artist of the Year Award in the U.K., and the Diapason d'Or de l’Année for young talent in France. Han Kang was celebrated for her deep insights into the pain of modern Korean history and the human mind, with works such as We Do Not Part, which addresses the Jeju April 3 Incident, and Human Acts, based on the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement. Yunchan Lim, the youngest winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn International , which had previously won six Emmy Awards, including Outstanding Drama Series.Squid Game. Meanwhile, anticipation was building ahead of the December 26 release of the second installment of Netflix's blockbuster drama series Chopin ÉtudesCompetition, received critical acclaim for his debut album.

However, at 10:27 p.m. on December 3, President Yoon Seok-yeol declared martial law on national television, stating his intention to “purge anti-state forces causing chaos.” This marked the first declaration of martial law in Korea in 45 years, the last being the expansion of martial law by Chun Doo-hwan’s military regime on May 17, 1980, following the assassination of President Park Chung-hee in a coup on October 26, 1979. News of the martial law declaration spread instantly through social media and shocked citizens, many of whom learned of it while riding the Seoul subway. Opposition leader Lee Jae-myung of the Democratic Party of Korea urged lawmakers to vote to nullify the declaration and called on citizens to gather in front of the National Assembly to protest.

Citizens flocked to Yeouido, where the National Assembly building is located. Armed martial law troops and police were deployed to the scene, and a helicopter landed on the roof of the National Assembly building. Angry citizens resisted by shouting “Oppose martial law!” at armed troops and armored vehicles attempting to blockade the Assembly. Members of the National Assembly bypassed the defensive barriers to enter the building. By 1:00 a.m. on December 4, 190 of the 300 Assembly members were present and unanimously passed a resolution demanding the lifting of martial law. This occurred just 2 hours and 34 minutes after the declaration. President Yoon lifted martial law six hours after the initial declaration and ordered the withdrawal of the deployed troops.

President Yoon faced widespread domestic and international criticism for what many considered an attempted coup d’état and an internal rebellion that violated Korea’s liberal democratic principles, constitutional procedures, and basic rights. Korean democracy was in crisis. In response, six opposition parties in the National Assembly jointly proposed an impeachment bill against Yoon. Citizens once again gathered in front of the National Assembly to protest. On December 7, the first vote on impeachment was aborted due to a mass walkout by the ruling People Power Party, which opposed the measure. However, the impeachment motion was reintroduced, and a second vote was held on December 14.

NYT: South Korea’s president is impeached

Approximately 2 million Koreans participated in rallies demanding impeachment. On December 14, the impeachment motion was dramatically passed with 204 votes in favor and 85 against. Protesters outside the National Assembly erupted in celebration, transforming the rally into a festive event. The culture surrounding the impeachment protests was noteworthy. The rallies featured K-pop performances and folk songs, while younger participants watched the film 12.12: The Day (Spring of Seoul), which depicts the 1979 coup d’état. Singer IU, girl group NewJeans, and director Park Chan-wook sent food to support the protesters. MissyUSA, an online community for Korean women in the United States, raised $14,000 to sponsor a fishcake soup truck. Numerous anonymous individuals prepaid for and supported the protesters with bread, coffee, hot packs, and other essentials. Singer Lee Seung-hwan performed on stage, energizing citizens with colorful cheering sticks. The impeachment protests resembled a vibrant festival, with the Christmas carol Feliz Navidad rewritten as Impeachment Is the Answer to further rally the crowd.

Ultimately, the "12.3 Emergency Martial Law" was overturned within just 2.5 hours. Korean citizens achieved the impeachment of an incumbent president through peaceful, non-violent protests. The president was suspended from office, and the power of a united citizenry, armed with the spirit of resistance, safeguarded Korean democracy.

2017. 3. 11. 20th candlelight vigil “Darkness cannot overcome light. Lies cannot overcome truth. The truth does not sink. We do not give up.”

*1st anniversary of candlelight: 3-minute video of Park Geun-hye’s fall, OhmyTV <YouTube>

Koreans are a “resistance nation.” Historically, we have learned to survive, as we have been constantly invaded by neighboring powers. Our people have resisted injustice through independence movements against foreign powers to democratization movements against dictatorship and corruption. The spirit of resistance is in our DNA. It is even said that Koreans’ forte, pièce de résistance (showpiece) is overcoming national crisis. The spirit of resistance originated from a consciousness of criticism.

2016-17 Candlelight Revolution

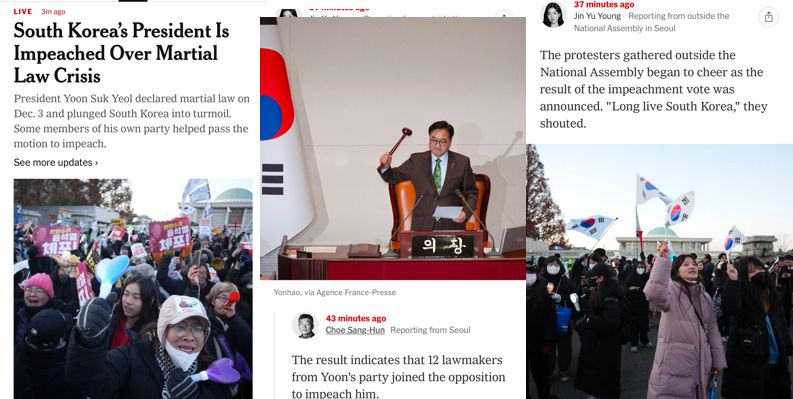

The Washington Post (from left), The New York Times, CNN on the 2017 candlelight protests in Korea.

#Washington Post: I’ll Teach You How to Impeach the President

The Washington Post published on May 19, 2017, two months after the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye (March 10, 2017): “South Koreans to Americans: We’ll teach you how to impeach a president.”

The newspaper reported, “South Koreans know how to impeach a president. Seventeen weeks of peaceful protest, combined with a parliamentary vote and a landmark court decision, led to the dismissal of Park Geun-hye in March amid a massive corruption scandal. Park is now behind bars and being tried on 18 charges, including bribery and extortion.” The paper continued: “Blogs are full of commentary on the similarities between Park and Trump — both took up the mantles of their fathers, both have ‘communication difficulties’ — and the differences in the two countries’ political systems.”

Along with this, the Washington Post emphasized: “This is quite a remarkable development since it was only 30 years ago that South Korea became a democracy while the United States has long considered itself an exemplar of democracy.” In addition, the Korean online community discussed the possibility of exporting their know-how about impeachment to the United States, and cited Kang Shin-ae's comment that “We need to export South Korean knowledge about impeaching a president and how to remove the president peacefully without shedding single drop of blood.”

*South Koreans to Americans: We’ll teach you how to impeach a president <The Washington Post>

#New York Times: Protests are peaceful, festive

On November 26, 2016, four months before President Park's impeachment, The New York Times reported on the massive protests, describing them as peaceful and almost festive. Journalist Choe Sang-Hun wrote, “Despite cold weather and the first snow of the season, a crowd that organizers estimated at 1.5 million gathered to denounce Ms. Park.” The article painted a vivid picture of the demonstrations: “Street vendors sold candles, mattresses, and hot snacks on Saturday, and a few roadside shops gave protesters free coffee. Buddhist monks beat wooden gongs as they marched. Mothers showed up with children, or with pet dogs wrapped in padded vests, and young couples bundled in winter coats sang along as loudspeakers blared catchy tunes calling for Ms. Park’s ouster.”

*Protest Against South Korean President Estimated to Be Largest Yet <The New York Times>

#Korean People - 2017 German Human Rights Award

The poster of the candlelight vigil for the President Park Geun-hye Resignation Movement held 23 times from October 26, 2016 to April 29, 2017.

In December 2017, a German political foundation, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), presented its Human Rights Award to the 17 million South Koreans who took part in candlelight rallies to call for then-President Park Geun-hye’s resignation over an influence-peddling scandal.

The organization’s representative in Korea, Sven Schwersensky, said: “The peaceful exercise of democratic participation and in particular the civic right of peaceful assembly are the essential components of democracy... In our view, the people’s candlelight demonstrations have given the whole world evidence of this important fact… At the time, authoritarianism was on the rise everywhere in the world, even in the western world.”

http://www.fes-korea.org

History of Resistance

March 1st Movement, University of Southern California University Libraries

Due to its fate as a peninsular country, Korea has become a prey for neighboring powers throughout its long history. The Tang, Sui, Yan, Wei, and Han dynasties attacked Korea during the Goguryeo period in succession, and Unified Silla (668-935 AD) was attacked by the Tang dynasty. During the Goryeo period (918–1392), Khitan, Mongolia, and Honggeonjeok invaded the country. And during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897), Koreans suffered large-scale wars and chaos, including the Imjin War (1592-1598), the Jeongyujaeran (1597-1598), and the Byeongjahoran (1636-1637). Meanwhile, the Korean people have learned how to survive.

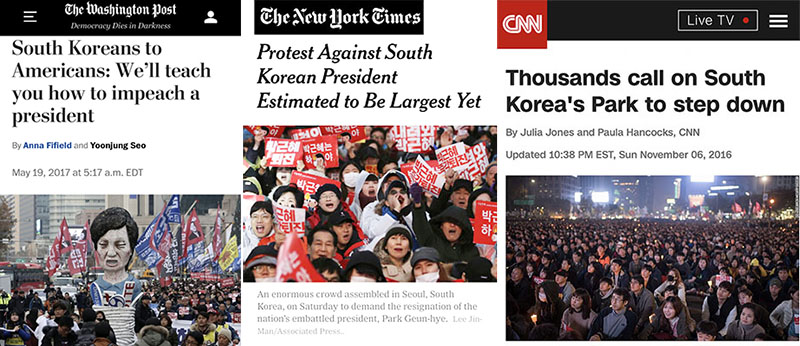

Koreans are a “resistance nation” that have resisted injustice, including the national liberation movement against foreign powers and for restoring sovereignty, and the democratization movement against dictatorship and corruption. During the Japanese colonial period, not only in Korea and Japan, but also in Manchuria, China, and Russia in the Far East, from the Shanghai Provisional Government and secret societies, to student movements, armed struggles, and cultural movements, non-violent and armed forces (medical soldiers, independent soldiers) resisted in all kinds of ways. The 3.1 Movement (“Sam-il” or March 1, 1919 movement) was a resistance movement in which the fighting spirit was gathered.

In modern times, Koreans have taken to the streets to demand the overthrow of dictatorships and the eradication of corruption. The April 19 Revolution of 1960, the May 18th Gwangju Uprising of 1980, the June Uprising of 1987, and the Candlelight Revolution of 2016 are all testaments to the Korean people's desire for democracy and their enduring spirit of resistance. The determination and resilience that have sent corrupt and incompetent leaders to prison are deeply ingrained in Korean DNA. It is even said that Koreans' greatest strength, their pièce de résistance, is their ability to overcome national crises.

#3.1 Independence Movement - March 1st Movement

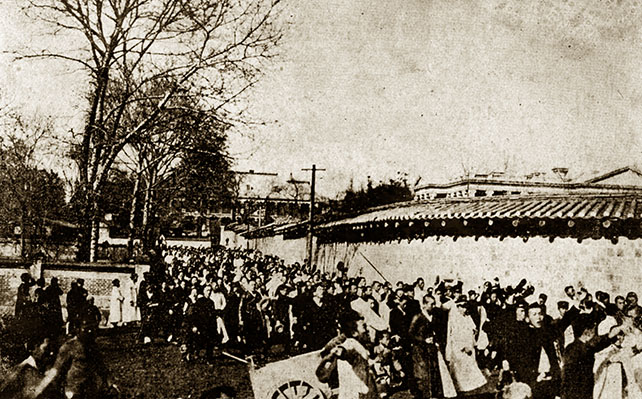

March 1st Movement, University of Southern California University Libraries

On March 17, 1919, the New York Times reported on the March 1st Movement in an article from Beijing.

“Tell of Japanese Cruelty to Koreans

American Missionaries Say There Is a Reign of Terror Throughout the Country.

Peking, March 17 - American missionaries report barbarous cruelties inflicted on the Koreans, of which they were witnesses. One observer declares that during the last ten days he has seen acts which seem like stories of the Germans in Belgium. Helpless women and children have been beaten, kicked, and stabbed, they say, as well as shot down by soldiers for no other crime than shouting ‘Hurrah for Korea!’”

*Tell of Japanese Cruelty to Koreans, Special to The New York Times

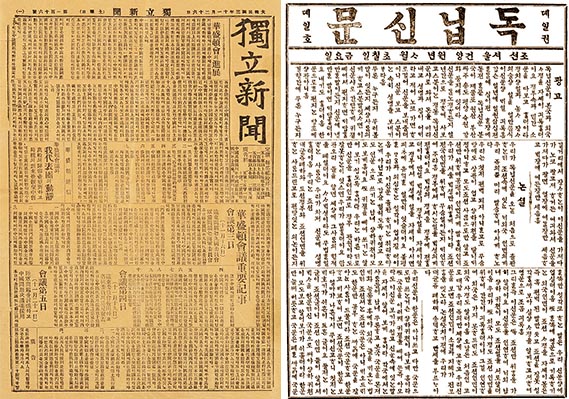

Independent Newspaper (left), the first private newspaper in Korea, launched on April 7, 1896. Independent Newspaper was founded in Shanghai on August 21, 1919 to inspire national ideology and unify the public mind.

“We declare that Joseon is an independent country, and that the Koreans are the masters of this country.”

On March 1, 1919, after 33 people read the Declaration of Independence at Taehwagwan in Seoul at 2 pm, hundreds of thousands of people shouted “Long live Korea” and the March 1st Movement began. Despite the oppression of Japanese imperialism, the nonviolent movement for national independence spread to all over the country, Gando, Siberia, Primorsky Krai (maritime territory), and the Americas. Over 2 million people participated in 1,491 protests in two months. At that time, the population was about 20 million. From the March 1st Movement to the end of December of that year, the total number of protests reached 3,200. The death toll was 7,907 (the actual number of deaths is estimated at 100,000), 15,850 were injured, 46,000 were arrested, and more than 10,000 were convicted. In addition, 715 houses, 47 church buildings and two schools were burned or destroyed.

The anti-Japanese struggle for the independence of the Korean people continued even after the March 1st Movement. In Korea, the peasant movement, the labor movement, and the student movement took root underground, and the armed struggle of the independence army continued in Manchuria and mainland China. Nonviolent and cultural anti-Japanese movements were also held, such as the Dong-A Ilbo’s “Japanese Flag Annihilation Incident” (1936), the Korean Language Society Incident (1942), and the Anti-Shinto Shrine Worship Movement.

The March 1st Movement did not immediately lead to independence. However, it has great significance in that it awakened the spirit of independence in Korean people and established the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, which became the cornerstone of the construction of an independent country. The Japanese Government-General of Korea served as an opportunity to shift from trespassing to a crafty cultural rule.

According to the National Archives of Korea, the March 1st Movement imprinted on the international community the aspiration and will of Koreans for freedom and independence. In addition to the May 4 Movement in China, it also influenced the independence movements of India, Egypt, Indochina, and the Philippines.

#Gandhi, Nehru, Joo Eun-rae and the 3.1 Movement

Educational thinkers of resistance and enlightenment during the Japanese colonial period (Go Won-seok et al., 2020)/ Forgotten heroes, independence activists (Jang Sang-gyu, 2017)/ Dictionary of 300 women independence activists (Lee Yun-ok, 2018)/ Daughter of Joseon, with a gun (Unhyeon Jung, 2016)

After the March 1st Movement, Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), the leader of the Indian independence movement of non-resistance and non-violence, started the British resistance movement in earnest. On March 21, 1919, the British enacted the infamous Rowlatt Act, which gave the Indian colonial government the power to unconditionally arrest and detain the anti-British activists by the police. Gandhi urged the Indians to engage in the Satyagraha struggle (non-violent resistance movement) against the repressive Rowlatt Act. On 30 March, British police opened fire on unarmed protesters in Delhi, which enraged Indians, who rioted.

At a Hindu festival on April 6, Gandhi emphasized mutual nonviolence by encouraging crowds to peacefully boycott British goods and burn British clothing instead of injuring or killing British people. He announced that he would take part in protests across India. The colonial government banned Gandhi from entering Delhi, but Gandhi refused to do so, leading to his arrest on 9 April. On April 13, British troops fired at Jallianwala Bagh, killing about 400 unarmed civilians and injuring more than 1,000.

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), the first Prime Minister of India, also paid attention to the March 1st Movement. From 1930 to 33, Nehru sent a total of 196 letters of world history to his only daughter, Indira Gandhi, from his prison cell. In his letter of December 30, 1932, he referred to the 3-1 movement. After introducing, “Joseon-this country came to be called by its old name. It means refreshing morning,” he wrote: “the struggle for independence continued for a long time and exploded several times. The most important of these was the uprising in 1919. The Korean people - especially young men and women - valiantly fought against the superior enemy. When the Korean national organization fighting to regain freedom formally declared independence and rebelled against the Japanese, they died countless times, and were imprisoned by the Japanese police numerous times and subjected to harsh torture. They sacrificed their lives for the sake of their ideals. The oppression of the Korean people by Japan was a bitter dark chapter in history. In Joseon, young women and girls, often as students or fresh out of college, played an important role in the struggle. If you listen to what you are doing, you will surely be moved.” Nehru’s prison letters were published as “Glimpses of World History” in 1934.

Zhou Enlai (1898-1976), the first Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of China, gave up studying at Meiji University in Japan and stopped by Joseon on his way home. Departing Shimonoseki in July 1919, passing through Busan and visiting Gyeongseong (Seoul), he wrote in his diary, “How did Joseon, 10 years after being occupied by Japanese colonial rule, carry out such an anti-Japanese independence movement?”

#May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement

Protesters march in vehicles looted from the military in Gwangju, 165 miles south of Seoul.

The New York Times reported on the front page of the Gwangju incident with a photo on May 22, 1980, under the title “Protesters Control South Korean City; At Least 32 Killed; New Cabinet Named in Seoul.”

The newspaper reported, “Tens of thousands of demonstrators, many waving seized rifles, iron bars, axes, pitchforks and even light machine guns, took control of this southwestern city today, the fourth day of anti-Government rioting that has cost the lives of at least 32 people.”

The era of Park Chung-hee, who came to power in a coup on May 16, 1961, ended with an assassination on October 26, 1979. The newly inaugurated President Choi Kyu-hah heralded the “Seoul Spring” by announcing that he would accept the people’s demands for democratization. However, within two months, Chun Doo-hwan’s new military force seized power again through a coup d’etat (the 12-12 military revolt).

The May 18th Gwangju Uprising in the spring of the following year was a social movement in which the awakened people resisted on a large scale. The Gwangju Uprising was reported as a “riot” by the new military and government media, but was formally defined as the “Gwangju Democratization Movement” after the inauguration of the 6th Republic.

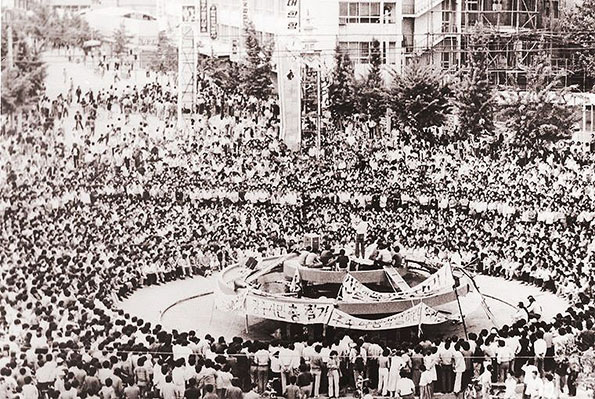

May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, UNESCO

From May 13, 1980, protests took place at 37 universities, including Seoul, Busan, Daegu, and Gwangju for two days, demanding the abolition of martial law. On the 15th, a student protest at Seoul Station paralyzed the city of Seoul. As of 24:00 on May 17th, after the new military government expanded martial law to the whole country, they imprisoned thousands of politicians and prominent figures such as Kim Dae-jung, Kim Young-sam, and Kim Jong-pil, and blocked the National Assembly with military forces.

On May 18, airborne forces were sent to Gwangju, and martial law forces occupied each university. When the paratroopers stopped the demonstration in front of Chonnam University, protestors regrouped at Gwangju Station, chanting “Release Kim Dae-jung,” “Remove the Remnants of the Yushin Party including Chun Doo-hwan and Shin Hyeon-hwak,” and “Abolish emergency martial law.” Students, middle-aged, and teenagers took part in the protests from 1 pm on the same day in the city center, including Geumnam-ro, due to the indiscriminate suppression of martial law forces. At around 4:50 pm, armored vehicles of the martial law force were surrounded by citizens, and taxi and bus drivers, urban poor, workers and farmers also joined the protest.

From May 20th, citizens seized weapons and the civil uprising turned into an armed struggle. A number of deaths occurred in gunfights between the civilian and martial law forces. On the 21st, the martial law forces withdrew from the Jeonnam Provincial Office after mass shooting at citizens in front of Chonnam National University and the Jeollanam-do Provincial Office.

The Citizens’ Army implemented a civil self-government system for a week from May 21st to 26th. The new military department announced that Gwangju was “absence of security,” and on the 27th, about 25,000 armed martial law forces mobilized tanks and helicopters to suppress it. At that time, it was reported that the new military department closely coordinated the suppression of the civil self-government by mobilizing airborne special forces with the United States.

The Gwangju Democratic Uprising came to an end in 10 days, and in August of that year, Chun Doo-hwan was inaugurated as the 11th President. According to the announcement on July 18, 1995 by the Seoul District Prosecutor’s Office and the Prosecutor’s Office of the Ministry of National Defense, there were 193 confirmed deaths (23 soldiers, 4 police, 166 civilians) and 852 wounded. According to UNESCO Human Rights Register data, 165 civilians were killed, 76 were missing, 3,383 were injured, and 1,476 were arrested, with a total of 5,100 people implicated.

Dong-A Ilbo, August 27, 1996

In 1995, on the 50th anniversary of liberation from Japanese colonial rule, the Special Act on Punishment of Perpetrators (no. 5029) was enacted, and former presidents Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo were tried as the main culprits of the 12-12 military uprising and the bloody suppression of the 5-18 Gwangju Democratization Movement.

Chun Doo-hwan was sentenced to death at the first trial for leading an insurrection, conspiracy to commit insurrection, taking part in an insurrection, illegal troop movement orders, dereliction of duty during martial law, murder of superior officers, attempted murder of superior officers, murder of subordinate troops, leading a rebellion, conspiracy to commit rebellion, taking part in a rebellion, and murder for the purpose of rebellion, as well as assorted crimes relating to bribery. And the Supreme Court reduced his sentence to life imprisonment in the second instance. Roh Tae-woo’s imprisonment was reduced from 22 years and 6 months to 12 years.

However, in December 1997, in the midst of the Asian financial crisis (IMF), President Kim Young-sam reached an agreement with President-elect Kim Dae-jung and released a special amnesty under the pretext of national dialogue. Their imprisonment was only eight months. In 1997, May 18 was designated as an official memorial day. In 2002, the Mangwol-dong Cemetery, where victims who participated in the Gwangju Uprising were buried, was elevated to a national cemetery with the enforcement of the Law on Special Cases for Bereaved Family Members.

In 2011, UNESCO registered materials related to the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement as a Human Rights Documentary Heritage (*1980 Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against Military Regime, in Gwangju).

The May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement left an indelible mark on South Korea’s history. In 1997, May 18 was designated as an official memorial day, and in 2002, Mangwol-dong Cemetery, where victims were buried, was elevated to a national cemetery. In 2011, UNESCO recognized the movement’s archives as a Human Rights Documentary Heritage (1980 Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against Military Regime in Gwangju).

The movement also inspired democratization efforts throughout Asia. UNESCO noted its influence on the Philippines’ People Power Revolution, Thailand’s Black May protests, and movements in China and Vietnam. It served as a catalyst for South Korea’s June Democratic Uprising of 1987, which ultimately led to the end of military rule.

May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, UNESCO

"The Gwangju Uprising was South Korea's Tiananmen crisis, profoundly shaping the resistance to dictatorship in the 1980s, paving the way for democratization in the 1990s, and leading to the conviction of those responsible for the massacre of innocent citizens in Gwangju."

Professor Bruce Cumings of the University of Chicago delivered a presentation titled "The Gwangju Uprising and U.S.-Korea Relations" at the 27th Anniversary International Academic Conference on the May 18 Democratization Movement, held at Chonnam National University on May 18, 2007. In his speech, Professor Cumings examined the U.S. government's complicity in the violent suppression of the May 18 Democratization Movement, holding it accountable for its failure to prevent the tragedy.

Pope John Paul II visited Gwangju in May 1984 during his Apostolic Journey to Korea. At a Mass held at Mudung Municipal Stadium, he acknowledged the profound wounds left by the tragedy and emphasized the need for reconciliation:

"I am keenly aware of the deep wounds that pain your hearts and souls from personal experiences and from recent tragedies, which are difficult to overcome from a merely human point of view, especially for those of you from Kwangju. For this reason, I hope you will be blessed by the grace of reconciliation."

Since 2000, the May 18 Memorial Foundation has annually presented the Gwangju Human Rights Award to individuals who have made significant contributions to human rights globally, ensuring that the spirit of the Gwangju Democratization Movement continues to inspire future generations.

#June 1987 Democratic Uprising

VIOLENT PROTESTS ROCK SOUTH KOREA, The New York Times (1987. 6. 11)

“Thousands of well-organized protesters, using bold hit-and-run tactics, fought with riot police in street battles that lasted through the night and into today. It was the worst street violence Seoul has seen in years. For brief periods Wednesday night, the demonstrators controlled some downtown streets, forcing police officers to retreat into buses before reinforcements arrived. Skirmishes continued into this afternoon between helmeted police officers firing tear-gas canisters and hundreds of rock-hurling students who refused to budge from the plaza outside Seoul’s Myeongdong Roman Catholic Cathedral. The protesters blocked off streets around the Cathedral with metal and wooden barricades. Several protesters were reported to have been injured in clashes with police in the plaza.”

— The New York Times

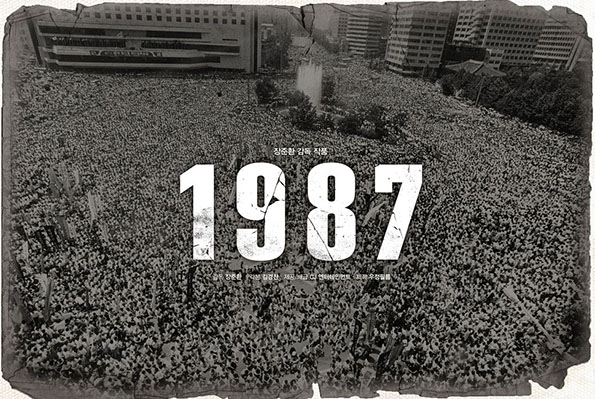

“1987: When the Day Comes” (2017), directed by Jang Jun-hwan

The June 1987 Democratic Uprising, inheriting the spirit of the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, was ignited by efforts to uncover the truth about the deaths of two young men, Park Jong-cheol and Lee Han-yeol. The movement ultimately achieved democratization, bringing an end to military rule.

At midnight on January 13, 1987, Park Jong-cheol, a third-year linguistics student at Seoul National University, was arrested at a boarding house by six investigators. In the Namyeong-dong investigation room of the National Police Agency, he was interrogated about the whereabouts of a senior in the university’s cultural research group. When Park refused to answer, the investigators subjected him to physical assault, electric shocks, and waterboarding. On January 14, he died under torture.

Dong-A Ilbo, January 19, 1987 <Reporter Yoon Sang-sam>

On January 16th, the Dong-A Ilbo published a special headline “A College Student who Died while being Investigated by the Police” (Reporter Hwang Yeol-heon). The report was based on the testimony of Park Jong-cheol’s uncle Park Wol-gil (“Jong-cheol was beaten in dozens of places and had blood bruises”) and his sister Eun-sook (“Chul-i was beaten to death by the police”).

Since February 1987, the Park Jong-cheol’s Pan-National Memorial and city protests have been held. President Chun Doo-hwan, who reached the end of his seven-year term in April, announced a “4-13 Defense of the Constitution” speech to suspend discussions on a Constitutional amendment and to transfer power according to the existing Constitution. On April 14, figures from all walks of life, including Catholic Cardinal Kim Sou-hwan, issued a statement criticizing the first Constitutional measure. At the Mass for the 7th anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising held at Myeongdong Cathedral on May 18, Father Kim Seung-hoon of the Catholic Priests Association for Justice (CPAJ), revealed the cover-up of the police’s torture and death of Park Jong-cheol. After that, protests calling for democratization began.

JoongAng Ilbo, June 11, 1987

News of his death was initially suppressed. The police reported that Park had died of shock during questioning. However, journalists uncovered the truth. On January 16, Dong-A Ilbo published a headline that read, “College Student Dies During Police Investigation,” quoting his uncle and sister, who confirmed signs of severe beating.

By February 1987, citywide protests and a pan-national memorial began to demand justice for Park Jong-cheol. Despite growing unrest, President Chun Doo-hwan, nearing the end of his seven-year term, delivered the “4·13 Defense of the Constitution” speech, rejecting constitutional reform and vowing to transfer power under the existing system. This move was met with widespread criticism, including from Cardinal Kim Sou-hwan.

On May 18, during a Mass marking the seventh anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising, Father Kim Seung-hoon of the Catholic Priests Association for Justice revealed the cover-up of Park Jong-cheol’s torture and death. This revelation sparked protests demanding democratization.

On June 9, during a demonstration at Yonsei University, Lee Han-yeol, a sophomore, was struck in the head by a tear-gas canister fired by riot police. The image of a fellow student supporting the unconscious Lee, captured by Reuters photojournalist Jeong Tae-won, was published on the front page of JoongAng Ilbo, galvanizing the uprising.

Large-scale protests erupted nationwide on June 10, organized by the National Movement for the Achievement of a Democratic Constitution. Despite the government’s attempt to deploy the military, including Chun Doo-hwan’s call for martial law, international pressure—particularly from the United States—prevented a violent crackdown. On June 26, simultaneous protests across 37 cities turned into a massive civil uprising, uniting students, workers, farmers, and office workers.

The breakthrough came on June 29, when presidential candidate Roh Tae-woo issued the June 29 Declaration, promising constitutional reforms, including direct presidential elections, amnesty for political prisoners like Kim Dae-jung, and press freedom. This marked a turning point, paving the way for democratic reforms. In October 1987, a constitutional amendment was passed, allowing for direct presidential elections.

Despite the progress, divisions between opposition leaders Kim Dae-jung and Kim Young-sam diluted their political influence, leading to Roh Tae-woo’s election as president.

Chosun Ilbo, July 10, 1987

The movement’s toll was profound. On July 9, Lee Han-yeol’s funeral drew 1.6 million mourners nationwide, marking the culmination of the June Democratic Uprising.

The June Uprising of 1987 remains a watershed moment in modern Korean history, ending military dictatorship and establishing a democratic republic where leaders are chosen by popular vote. It also diversified Korea’s social movements, inspiring initiatives in environmental protection, consumer rights, gender equality, and human rights.

#2008 U.S. Beef Candlelight Protests

June 10, 2008 Mad Cow Disease Candlelight Demonstrations

While the June 1987 Uprising was ignited by the exposure of Park Jong-cheol's death by water torture and a photograph of Lee Han-yeol being struck by a tear gas grenade, the catalyst for the April 2008 Mad Cow Disease Candlelight Protests was an investigative report aired on MBC-TV's PD Note titled "Is American Beef Really Safe from Mad Cow Disease?"

The controversy began when President Lee Myung-bak signed the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement with President George W. Bush on April 19, 2008, which permitted the import of U.S. beef, including cuts from cattle over 30 months old—an age considered riskier for potential contamination with mad cow disease. Public concern exploded after PD Note aired on April 27, raising alarms about the safety of U.S. beef and its potential health risks. This triggered widespread opposition to U.S. beef imports, culminating in a rally organized by the National Movement Headquarters for the Impeachment of Lee Myung-bak on May 2. The protests evolved into the Candlelight Cultural Festival, featuring performances by celebrities such as Kim Jang-hoon and Yoon Do-hyun, which encouraged families to participate.

The demonstrations reached their peak during the June 10 protest, coinciding with the commemoration of Korea's June 10, 1926, National Independence Movement. In response to mounting public outrage, President Lee Myung-bak issued a public apology on June 18. However, protests continued until August 15, concluding with a final candlelight vigil in Daehak-ro attended by 5,500 people. A teenage schoolgirl, Han Chae-min, holding a lit candle, became an enduring symbol of the anti-U.S. beef protests.

Over 106 days, from May 2 to August 15, 2008, a total of 2,398 candlelight demonstrations were held, drawing 932,000 participants. Of these, 1,476 protesters were charged, and 1,258 were prosecuted. Through these candlelight protests, the Lee Myung-bak government secured quarantine sovereignty in additional negotiations for importing American beef, allowing it to suspend imports at any time in the event of an outbreak of mad cow disease in the United States, and decided to import only beef from cattle under 30 months of age.

Culture of Resistance

#Era of forbidden songs, culture of resistance in the 1970s

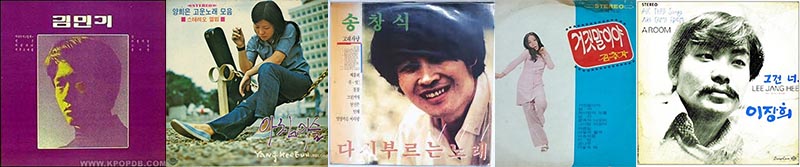

Kim Min-ki, Yang Hee-eun, Song Chang-sik, Kim Chu-ja, Lee Jang-hee... The songs of representative singers in the 1970s were banned by the Yushin (The Revitalizing Reform) regime.

The history of banned songs in Korea dates back to the origins of popular music in the country. During the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945), the Japanese Government-General of Korea banned songs like Arirang, Bongseonhwa (Touch-Me-Not), and Tearful Tuman River due to their potential to evoke nationalistic sentiment. After Korea's liberation, songs by North Korean writers faced similar prohibitions. The introduction of the Act on Sound Records in 1967 formalized pre-censorship in the country.

Youth culture that resisted the conservative mindset of the older generation became a symbol of defiance. In the United States, cultural movements such as the "Beat Generation" after World War II and the "Hippies" during the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s led similar waves of resistance. In Korea, the 1970s saw the rise of counterculture, spearheaded by young people disillusioned by the re-establishment of military dictatorship.

The vibrant youth culture of the 1970s—characterized by long hair, blue jeans, mini-skirts, acoustic guitars, draft beer, and music cafes—was eventually stifled by a wave of song bans and cannabis crackdowns enforced by the military regime. Under Emergency Decree No. 9 in 1975, 223 popular songs, including Morning Dew, Whale Hunt, Give Me Some Water, Why Call Me?, That's You, Beautiful Woman, It's a Lie, and To the Land of Happiness, were banned for allegedly being harmful to public morals. Folk and rock pioneers like Kim Min-ki, Han Dae-su, Lee Jang-hee, Yang Hee-eun, Song Chang-sik, and Shin Joong-hyun were silenced, plunging popular culture into a dark age as creative freedom was stifled.

President Park Chung-hee's authoritarian Yushin System censored popular songs under the pretext of "establishing a sound national life and social ethos." In 1975, the Korean Arts and Culture Ethics Committee banned songs for reasons including potential harm to national security, uncritical imitation of foreign trends, defeatism, self-harm, lamentation, and excessive sensuality or decadence. This censorship severely curtailed artistic expression.

A poignant example of the era's resistance can be found in the lyrics of Kim Min-ki's Morning Dew (1971), a song that symbolized resilience and hope:

After the night's long vigil, on every blade of grass,

Morning dew clings, finer than the finest pearls.

When sorrow gathers like clouds in my heart,

I climb the hill at dawn and find a small smile.

The sun rises, burning over the silent graves,

And the midday heat becomes my trial to bear.

Now, I journey into the wilderness,

Casting off all sorrow, leaving it behind.

The suppression of songs like Morning Dew highlighted the regime's fear of music as a medium for resistance and solidarity. However, the demand for freedom and democracy ultimately prevailed.

Following the June 29 Declaration in 1987, announced by then-presidential candidate Roh Tae-woo in response to the democratization movement and demands for direct presidential elections, the Ministry of Culture and Public Information lifted the ban on 185 songs, including Morning Dew and Camellia Lady.

This marked the end of an era of censorship and the beginning of a cultural renaissance, as long-silenced voices were finally able to resonate with the public once more.

#Gwangju Democratization Movement and Minjung Art

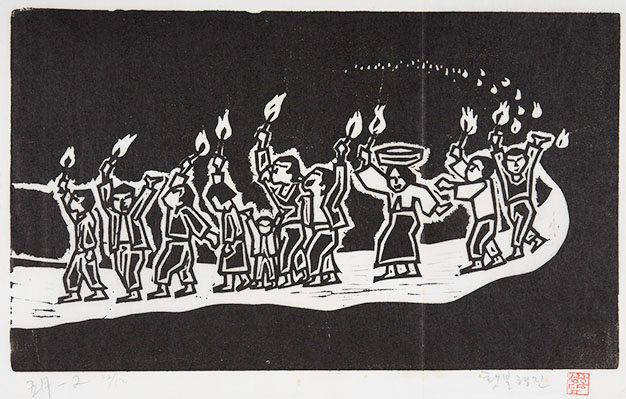

Hong Seong-dam, May Torch Parade, woodcut 25.3 x 43 cm 1983. Seoul Museum of Art Collection

"The pen is mightier than the sword." Yet, an image can be even more powerful than words.

The great painters in art history did not escape from reality and did not turn away from the ongoing tragedy. Francisco Goya's painting “The Massacre of 3 May 1808 (El tres de mayo de 1808),” (1814), is a dramatic depiction of the French occupation of Spain and the massacre of civilians in Madrid in retaliation after the rebels rose up against the French. Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937) tells the story of a series of bombings of the town of Guernica in the Basque region of Spain by Nazi German forces supporting General Franco during the Spanish Civil War in April 1937, killing about 1,600 people, one-third of the population.

After the Gwangju Democratization Movement in 1980, Korean progressive artists began to participate in art movements and the Minjung Art was born. It focuses on historical events such as the Donghak Peasant Revolution, the Korean War, the April 19 Revolution, and the May 18 Gwangju Uprising, as well as the issue of unification, the conflicts of capitalist society, the labor issues, peasants and women’s human rights.

However, Minjung Art was suppressed under Chun Doo-hwan’s dictatorship. In July 1985, 36 art works at the exhibition “1985, the Power of 20 Korean Art” held at the Arab Cultural Center were forcibly confiscated by the police, 19 people were forcibly taken into custody, and 5 people were arrested.

In 1994, “15 Years of Minjung Art” was held on a large scale at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul without any political interruptions. On the website of the Tate Modern in London, “Minjung Art” is explained:

“Minjung art was a South Korean socio-political art movement that emerged in 1980 after the Gwangju Massacre, in which some 200 peaceful demonstrators were killed by government troops”

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/m/minjung-art

Minjung Art remains a testament to the enduring power of art to challenge authority, inspire resistance, and provide a voice to the oppressed. It stands as both a historical record of struggle and a symbol of hope for a more equitable future.

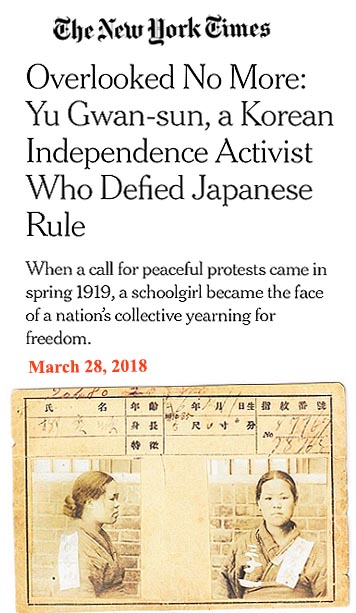

#New York Times published the obituary of Yu Gwan-sun in March 2018

Overlooked No More: Yu Gwan-sun, a Korean Independence Activist Who Defied Japanese Rule, NYT

The New York Times published an obituary (“Overlooked No More: Yu Gwan-sun, a Korean Independence Activist Who Defied Japanese Rule”) on March 28, 2018, on the hero of the March 1st Movement, Yu Gwan-sun (1902-1920).

Since its founding in 1851, the New York Times has been dominated by white men in its obituaries. In celebration of International Women’s Day on March 8, 2018, “Overlooked No More” added historically notable obituaries of women, blacks, and other minorities. And on March 28, 2018, the life of martyr Yu Gwan-sun was reported. This is the obituary of Yu Gwan-sun reported in 1920, which is known to the West for the first time in nearly 100 years.

The obituary began, “When a call for peaceful protests in support of Korean independence came in spring 1919, a 16-year-old girl named Yu Gwan-sun became the face of a nation’s collective yearning for freedom. Yu was a student at Ewha Hakdang in Seoul, which was established by American missionaries as the first modern educational institution for women in Korea. On March 1, 1919, Yu and four classmates joined others taking to the streets with cries of ‘Mansei!’ (‘Long live Korean independence!’) in one of the earliest protests against Japanese colonial rule. Amid the demonstration, the Declaration of Independence — written by the publisher Choe Nam-seon and signed by 33 Korean cultural and religious leaders — was recited at Seoul’s Pagoda Park.”

The Times cited her diary in prison “Even if my fingernails are torn out, my nose and ears are ripped apart, and my legs and arms are crushed, this physical pain does not compare to the pain of losing my nation. ... My only remorse is not being able to do more than dedicating my life to my country.”

In August 2015, Yukio Hatoyama, a onetime leader of Japan, visited Seodaemun, where Yu was tortured and killed by the Japanese police in 1920. He said “as a former prime minister, as a Japanese citizen and as a human being, I am here today to offer my sincere apologies, from the bottom of my heart, to those who were tortured and were killed here.”

#Blacklisted Creatives: Bong Joon-ho, Hwang Dong-hyuk, and Han Kang

What do Parasite director Bong Joon-ho, who swept the Cannes Palme d’Or and four Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Screenplay, Best Director, and Best International Feature Film); Squid Game creator Hwang Dong-hyuk, who won six Emmy Awards (including Best Director and Best Actor); and novelist Han Kang, recipient of the 2016 International Booker Prize and the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, have in common?

These internationally acclaimed figures in film, television, and literature were all blacklisted by the South Korean administrations of Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye. Bong Joon-ho faced scrutiny for his socially critical films, including Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Snowpiercer (2013). A 2008 National Intelligence Service (NIS) report criticized The Host for “highlighting anti-Americanism and government incompetence, shifting public consciousness to the left.” Similarly, Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Silenced (2011) was targeted in a 2013 NIS report for depicting civil servants and police as “corrupt and incompetent,” claiming the film fostered negative public perceptions. Even Park Chan-wook’s Joint Security Area (2000) was blacklisted for its controversial portrayal of inter-Korean relations.

Han Kang was blacklisted by the Park Geun-hye administration for her novel Human Acts (2014), which confronted the atrocities of the 1980 Gwangju Uprising. When Han won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016, it was reported that Park broke with precedent by refusing to send her a congratulatory message.

Bong Joon-ho, a graduate of Yonsei University’s Department of Sociology, and Hwang Dong-hyuk, an alumnus of Seoul National University’s Department of Journalism, reflect a deep-rooted spirit of resistance and critical awareness in Korean society. Bong’s Parasite critiques capitalism, exposing the moral decay and widening economic disparities within society, while Hwang’s Squid Game employs a brutal survival competition to highlight the dehumanizing effects of social inequality. Both works center on marginalized individuals grappling with systemic exploitation.

Han Kang, a graduate of Yonsei University’s Korean Literature program, has similarly used her writing to amplify the voices of those affected by historical trauma. In Human Acts, she delved into the brutality of the Gwangju Uprising, and in her 2021 novel We Do Not Part, she explored the lingering scars of the 1948 Jeju April 3 Massacre.

Bong Joon-ho has consistently paired artistic excellence with incisive social commentary. After winning Best Foreign Language Film at the 77th Golden Globe Awards in January 2020, he famously stated, “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films,” challenging American audiences to embrace international cinema.

Later, in an October 2019 interview with New York Magazine, he remarked, “The Oscars are not an international film festival. They’re very local,” critiquing the American-centric focus of the Academy Awards. Despite this, Bong made history in 2020 when Parasite became the first non-English-language film to win Best Picture, along with three other Oscars.

*Youn Yuh-Jung Wins Best Supporting Actress <YouTube>

Veteran actress Youn Yuh-jung, who won both the 2021 BAFTA and Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Minari, also embodied a bold and humorous critique in her acceptance speeches. At the BAFTAs, she quipped, “Every award is meaningful, but this one, especially being recognized by British people—known as very snobbish—makes me very privileged and happy.” Her remark went viral, earning widespread praise for its candid wit.

At the Academy Awards, Youn once again captivated audiences, humorously addressing presenter Brad Pitt: “Mr. Brad Pitt, finally. Nice to meet you. Where were you when we were filming in Tulsa?” The line drew laughter and admiration, with The New York Times calling her speech a highlight of the night and The Guardian hailing her as “a champion.”

These blacklisted artists—Bong Joon-ho, Hwang Dong-hyuk, and Han Kang—exemplify the resilience of Korean creators who, despite institutional resistance, continue to challenge societal norms and produce groundbreaking work that resonates globally. Their success underscores the transformative power of storytelling to confront injustice, inspire empathy, and spark meaningful change.

#MissyUSA Members Criticize the Korean Government in the NYT

Koreans abroad also exemplify a profound sense of resistance and critical thinking. The Sewol Ferry disaster on April 16, 2014, claimed 304 lives, including 250 high school students who were on a school trip. This tragic incident sent shockwaves through Korean communities worldwide, leaving behind deep sorrow, pain, and anger.

In response, members of MissyUSA.com, a Korean American women’s community website, organized a fundraising campaign. Within just ten days, more than 4,000 members participated, raising over $160,000. These funds were used to publish two full-page advertisements in The New York Times in May and August of that year, condemning the incompetence and corruption of the Park Geun-hye administration.

The ads, titled “Bring the Truth to Light” and “South Korean Government Sank Sewol Ferry, but Cannot Sink the Truth,” expressed a fervent call for justice and accountability. They embodied the desire of Korean women abroad for democracy in their homeland and reflected the enduring spirit of resistance and criticism that defines Koreans as a people.

A Nation of Resistance

Koreans have long been a "resistance nation," with a history shaped by survival and defiance in the face of adversity. Repeated invasions and challenges from neighboring powers have forged a collective resilience. Koreans have resisted oppression, from independence movements against colonial rule to democratization struggles against dictatorship and corruption.

This spirit of resistance is deeply embedded in the cultural DNA of Koreans. It is often said that the strength of the Korean people—their “pièce de résistance” (showpiece)—lies in their ability to overcome national crises. This indomitable will to confront injustice stems from a deeply rooted critical consciousness and an unwavering resolve to demand truth and accountability.

Sukie Park

A native Korean, Sukie Park studied journalism and film & theater in Seoul. She worked as a reporter with several Korean pop, cinema, photography and video magazines, as a writer at Korean radio (KBS-2FM 영화음악실) and television (MBC-TV 출발 비디오 여행) stations, and as a copywriter at a video company(대우 비디오). Since she moved to New York City, Sukie covered culture and travel for The Korea Daily of New York(뉴욕중앙일보) as a journalist. In 2012 she founded www.NYCultureBeat.com, a Korean language website about cultural events, food, wine, shopping, sightseeing, travel and people.

33 Keys to Decoding the Korean Wave, Hallyu

Beyond BTS, Parasite & Squid Game

CONTENTS

#Prologue: 국풍인가, 국뽕인가 Dynamic Korea, Sparkling Koreans

#1 비빔밥 정신 The Spirit of Bibimbap

#2 빨리빨리 문화 The Culture of ppalli Ppalli

#3 눈치의 달인들 Homo Nuncius Korean

#4 저항의 민족 People of Resistance

#5 한(恨)과 한국영화 르네상스 Country of Trauma, Culture of Drama

#6 쇠젓가락 유전자 The Magic of Metal Chopsticks

#7 세탁의 장인들 Masters of Laundry

#8 복(福)을 싸드립니다: 보자기, 보따리와 보쌈 Bojagi, Bottari, Bossam

Joseon, Corea, Korea

#10 호머 헐버트와 세계인들의 한글예찬 Hangul, the Korean Alphabet

#11 '오징어 게임'과 '놀이의 왕국' 코리아 'Squid Game' and Homo Ludens Koreans

#13 음주가무-먹고 Eat

#14 음주가무-마시고 Drink

#15 음주가무-노래하고 Sing

#16 음주가무-춤추고 Dance

The Power of Koreans

#17 미 태권도의 대부 이준구 대사범 The Father of American Tae Kwon Do, Jhoon Rhee

#20 82년생 김지영 도서 한류 열풍 K-Books and Korean Feminism

#24 '비디오 아트의 선구자' 백남준과 후예들 Nam June Paik and His Descendants

#25 K-클래식: 정경화에서 임윤찬까지 콩쿠르 강국 The Korean Musical Mystery

#26 비틀즈 Vs. 방탄소년단 The Beatles vs. BTS

#27 입양한인 예술가들 K-Adoptees Shine in the Art World

K-Culture Renaissance

#28 K-Food 한식 엑스타시 The Wide Spectrum of Korean Taste Buds

#29 K-Art 단색화 부활하다 The Revival of the Korean Monochrome Painting

#31 K-Beauty 성공신화 The Myth of K-Beauty

#32 K-Spa '한국 스파의 디즈니랜드' 찜질방 Jjimjilbang, The Disneyland of Korean Spa

#33 K-Quarantine 기생충, 킹덤과 코로나 팬데믹 K-Quarantine: 'Parasite' 'Kingdom' and Pandemic

#Epilogue