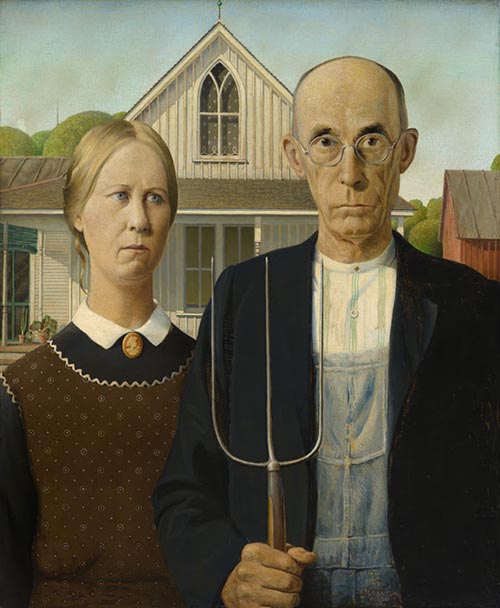

| NEW YORK, December 20, 2017—The upcoming Grant Wood retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art will reassess the career of an artist whose most famous work, American Gothic—one of the most indelible emblems of Americana and perhaps the best-known work of twentieth-century American art—will be making a rare voyage from the Art Institute of Chicago for the occasion. Organized by Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, with senior curatorial assistant Sarah Humphreville, this exhibition is Wood’s first museum retrospective in New York since 1983 and only the third survey of his work outside the Midwest since 1935. It will be on view in the Whitney’s fifth-floor Neil Bluhm Family Galleries from March 2 through June 10, 2018. Grant Wood (1891–1942) achieved instant celebrity following the debut of American Gothic at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930. Until then, he had been a relatively unknown painter of French-inspired Impressionist landscapes in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. His relatively short mature career, from 1930 to 1942, spanned a tormented period for the country, as the United States grappled with the aftermath of an economic meltdown and engaged in bitter debates over its core national identity. What emerged as a powerful strain in popular culture during the period was a pronounced reverence for the values of community, hard work, and self-reliance that were seen as fundamental to the national character, embodied most fully in America’s small towns and on its farms. Wood’s romanticized depictions of a seemingly more innocent and uncomplicated time elevated him into a popular, almost mythic figure, celebrated for his art and promotion of Regionalism, the representational style associated with the Midwest that dominated American art during the Depression.

As Barbara Haskell has noted, “The enduring power of Wood’s art owes as much to its mesmerizing psychological ambiguity as to its archetypal Midwestern imagery. An eerie silence and disquiet runs throughout his work, complicating its seemingly bucolic, elegiac exterior. Notwithstanding Wood’s desire to recapture the imagined world of his childhood, the estrangement and isolation that came of trying to resolve his loyalty to that world with his instincts as a shy, sexually closeted Midwesterner seeped into his art, endowing it with an unsettling sadness and alienation. By subconsciously expressing his conflicted relationship to the homeland he professed to adore, Wood created hypnotic works of apprehension and solitude that may be a truer expression of the unresolved tensions of the American experience than he might ever have imagined, even some seventy-five years after his death.”

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables brings together the full range of Wood’s art, from his early Arts and Crafts decorative objects and Impressionist oils through his mature paintings, murals, works on paper, and book illustrations. The exhibition reveals a complex, sophisticated artist whose image as a farmer-painter was as mythical as the fables he depicted in his art.

“This exhibition is an interrogation—not a reification—of stereotypes, values, and reputations,” writes Adam D. Weinberg, the Whitney’s Alice Pratt Brown Director, in his foreword to the exhibition catalogue. Rather than celebrating a nostalgic American past that never was, the exhibition is “a quest to understand how a remarkable artist created mythic images, images that are not as unequivocal or as unambiguous as some might think or, yet, as some might wish…What one discovers, looking deeply into Wood’s paintings, is that, for all their apparent clarity and precision of style, in the best of them what is depicted is not at all straightforward. The images put forth are often conflicting and ambiguous. They reveal a collision of amplified meanings, sublimated feelings, and layered evidence.”

Wood began his career as an Arts and Crafts decorative artist. Even after he shifted to fine arts, he retained the movement’s ideology and pictorial vocabulary. To it, he owed his later use of flat, decorative patterns and sinuous, intertwined organic forms as well as his belief that art was a democratic enterprise that must be accessible to the average person, not just the elite. Wood’s training in the decorative arts began early. He studied at the Handicraft Guild in Minneapolis for two summers after graduating from high school before moving to Chicago to join the Kalo Arts and Crafts Community house. In 1914, he opened the Volund Crafts Shop with a fellow craftsman and began to exhibit his jewelry and metalwork in the Art Institute of Chicago’s prestigious decorative arts exhibitions. Despite this recognition, commercial success eluded him and he closed the shop and returned to Cedar Rapids in 1916 to begin his painting career. The decision did not mean the end of his work in decorative arts, however, as is evident from the 1925 Corn Cob Chandelierincluded in the exhibition and the 1928 stained-glass window he designed for Cedar Rapids’ Veterans Memorial Building, replicated at half-scale in the exhibition. Even after the success of American Gothic, he continued designing objects for popular use. His Spring Plowing fabric design, armchair and ottoman, Steuben glass vase, eight book covers and illustrations for two books—all made after 1930—are also included in the exhibition.

At the start of his career, Wood believed in the cultural superiority of Europe, as did many other Americans. Consequently, he went abroad four times between 1920 and 1928 for a total of twenty-three months, primarily studying the work of the French Impressionists, whose loose brushwork he used in the first two decades of his career to paint what he later called “Europy-looking” subjects. His assimilation of the style served him well; by the early 1920s, he was the city’s leading artist, selling his paintings to its residents and executing commissions in a variety of styles according to the given project’s needs. Three of Wood’s commissioned paintings, along with examples of his Impressionist works, are included in the exhibition.

By the late 1920s, Wood had come to believe that American art needed to break free from Europe and that the emergence of a rich American culture depended on artists expressing the specific character of their own regions. For him, it was Iowa, whose rolling hills he used as the background for his earliest mature portraits. In Europe, he had admired Northern Renaissance painting by artists such as Hans Memling and Albrecht Dürer. His realization that the hard edge precision and meticulous detail in their art could convey a distinctly American quality, especially suggestive of the Midwest, became the foundation of his mature style.

Wood brought to his portraits and landscapes his belief that democratic art necessitated universal and timeless story telling. He achieved this in his portraits by painting types rather than individuals and by including images that suggested something about the life and character of the depicted subject. He left these images intentionally ambiguous, making the stories they suggest so enigmatic that they defy ready explanation; they are puzzles to be deciphered by viewers based on their individual attitudes and predilections.

Wood believed that people are psychologically formed in the first twelve years of life and that everything they experience later is tied up with those childhood years. He often spoke of the experiences of his early years on his family’s farm as “clearer than any I have known since.” Not surprisingly, his landscapes do not depict Midwestern farm life in the 1930s, but instead, portray his idealized memories of the 1890s farm he lived on as a young boy before moving to Cedar Rapids with his family following the death of his father. His desire was not so much to celebrate a world that was becoming extinct as to recapture the idyllic, re-imagined dream world of his own childhood. In his hands, the Midwestern farm became an Arcadian fantasy of undulating, swollen shapes and decorative embellishments whose tumescent abundance was sufficiently polymorphous to be read as both masculine and feminine. Yet Wood unconsciously challenged this evocation of sensuality and fecundity by employing rigid geometries, shellac-like surfaces and sharp, unnatural light that yielded landscapes that appear curiously still, a dollhouse world of estrangement and solitude.

Wood’s hard edge style and nostalgic subject matter made him one of America’s most revered artists during the 1930s, with a host of artists around the country imitating his art, especially his murals. Seen as paradigmatic images of prosperity and shared purpose, these works served as models for the scores of murals commissioned by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal art programs during the Depression. With their subdued colors and monumental, frozen figures, Wood’s murals evoke the early Renaissance art of Fra Angelico and Giotto that he had admired in Europe. Examples of all of Wood’s murals, both realized and unrealized, will be in the exhibition, including a projected film of his two large-scale PWAP murals at Iowa State University at Ames.

The rise of fascist powers in Europe in the late thirties turned Wood’s attention to the fate of democracy. Worried that America might be vulnerable to outside aggression, he set out to inspire the public to defend the country in case of attack by rekindling national pride. To do so, he planned to depict a series of American folktales, highlighting their fictional aspect to avoid the chauvinism associated with fascism. The first was Parson Weems’s tale of George Washington as a child confessing to having chopped down his father’s cherry tree. The growing crisis in Europe shifted Wood’s focus. Faced with Nazi victories over the Allies in the first years of World War II, he accelerated his efforts to awaken the country to what it stood to lose by depicting what he called the “simple, everyday things that make life significant to the average person.” He completed only two works in the series—Spring in the Country and Spring in Town—before his death of pancreatic cancer on February 2, 1942, two hours before he would have turned fifty-one.

|