보스턴미술관 프리다 칼로 전시(2/27-6/16)

Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular

February 27-June 16, 2019

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Throughout her entire career, Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) avidly collected traditional Mexican folk art—arte popular—as a celebration of Mexican national culture. She drew inspiration from these objects, seizing on their political significance after the Mexican Revolution and incorporating their visual and material qualities into her now-iconic paintings. The first-ever Kahlo exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular focuses on the artist’s lasting engagement with Mexican folk art, exploring how her passion for objects such as decorated ceramics, embroidered textiles, children’s toys, and devotional ex-votopaintings shaped her own artistic practice. Eight Kahlo paintings—including important loans from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin—are brought together with approximately 40 representative examples of arte popular, many on loan from the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA), as well as photographs and important illustrated publications from the period. On view from February 27 through June 16, 2019 in the Saundra B. and William H. Lane Galleries, located in the MFA’s Art of the Americas Wing, the exhibition features interpretation in English and Spanish. “Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular” is generously supported by the Darwin Cordoba Fund for Latin American Art and Kristin and Roger Servison. Media partner is El Planeta.

“We’re thrilled to bring our visitors the MFA’s first exhibition on Kahlo, which provides a distinctive view of the artist,” said Layla Bermeo, Kristin and Roger Servison Assistant Curator of American Paintings. “While many exhibitions focus on the artist’s biography and interpret her paintings as direct illustrations of life events, our exhibition brings fresh attention to Kahlo as an ever-evolving and ambitious painter, who actively responded to arte popular. It also opens broader discussions about the influences of anonymous folk artists on famed modern painters.”

Powerfully linking art and politics, the term arte popular was used publicly for the first time in 1921—one year after the end of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). Following this devastating civil war, government officials and artists played overlapping roles, trying to construct patriotic histories and images that could unite Mexico’s divided peoples. Kahlo herself was not a folk artist, but drew inspiration from ceramics, carvings and other handmade objects made in rural communities. She and other urban intellectuals championed these works of arte popular as expressions of true mexicanidad, or Mexican national culture, and as celebrations of Mexico’s indigenous and working-class people. By examining some of the social and political ideas of the post-Revolutionary period, this exhibition offers contexts for both Kahlo’s paintings and arte popular, as well as explores dialogues between the two.

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted by an eight-foot-tall “Judas” Figure (2018) commissioned by the MFA from contemporary artist Leonardo Linares, whose grandfather Pedro Linares made similar papier-mâché sculptures for Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera. Comparable Judas figures, along with other objects in Kahlo’s collection of arte popular, can be seen in photographs taken around 1940 by Bernard Silberstein at the Casa Azul—Kahlo and Rivera’s shared home in Coyoacán, then a village outside Mexico City. The photographs are on loan from the Detroit Institute of Arts and displayed in the exhibition. The introductory section also provides historical context for the display of arte popular at the MFA, highlighting a selection of objects that were shown at the Museum around 1930 as part of Mexican Arts, an exhibition that traveled to 13 institutions across the U.S. Following the introduction, Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular is organized thematically into five sections.

Exhibition Overview

Art of the People / Arte del Pueblo

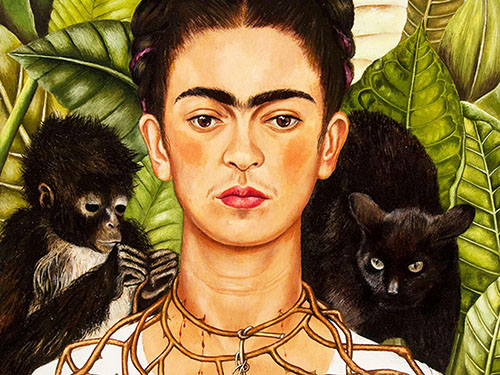

Kahlo collected arte popular as an act of national pride, to show her knowledge and appreciation of Mexican artists working outside European-style institutions. Around the same time that muralists promised to liberate painting from easels and make art accessible to the public, arte popular was defined as a form of art for the people, by the people. This section brings together for the first time two paintings from different periods in Kahlo’s career: the MFA’s recently acquired Dos Mujeres (Salvadora y Herminia) (1928), which in 1929 became the first painting sold by the artist, and the iconic Self-Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace (1940, Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin). Painted more than a decade apart, these works demonstrate the progression of Kahlo’s painting practice while also showing her politics and dedication to Mexico’s diverse histories, peoples, plants and animals. Dos Mujeres is a dignified portrait of two mixed-race women who were muchachas, or domestic workers, in Kahlo’s mother’s household. The dense foliage background of the painting evokes the organic patterns on many works of arte popular, such as a Burnished Jar (about 1930, San Antonio Museum of Art, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Mexican Folk Art Collection) decorated with explosively bright flowers and leaves. A lush foliage background also appears in Self-Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace, in which the artist poses herself alongside imagined creatures and her own pet monkey. The painting is shown near two ceramic arte popular monkeys (about 1930, San Antonio Museum of Art, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Mexican Folk Art Collection)—one is a whistle and the other is meant to hold the alcoholic beverage mescal. They exemplify everyday arte popular objects that unified beauty and function, representing longstanding artistic traditions and patterns of use within rural communities.

Aesthetics of Childhood / Estéticas de la Infancia

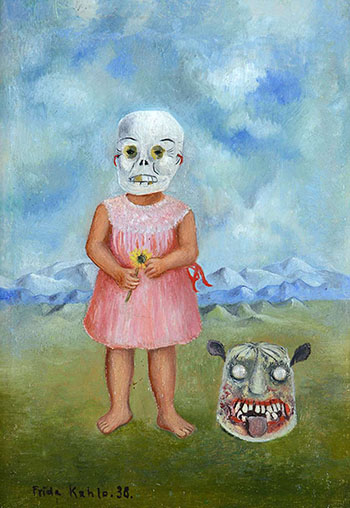

Kahlo was fascinated by the world of children, sharing this interest with many other Mexican modernists. Toys were one of the most prominent categories of arte popular—dolls, wooden marionettes and ceramic animals captivated collectors with their sculpted details and sophisticated color combinations, all rendered in miniature. The allure of such small objects perhaps helped Kahlo see the monumental visual power that could be developed in small dimensions. Measuring about six by five inches, Kahlo’s painting Girl with Death Mask (She Plays Alone)(1938, Nagoya City Art Museum) depicts a child—likely the artist herself—wearing a pink, lace-trimmed dress and hiding her face behind the rounded yellow eyes and clenched teeth of a skeleton mask. The jaguar mask next to her is connected to notions of physical and supernatural strength. The painting is displayed alongside a wooden Jaguar Mask (late 19th century, San Antonio Museum of Art, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Mexican Folk Art Collection) that is representative of the type collected by Kahlo. Additional works on view in this section include the drawing Untitled (Portrait of Girl with Orange Bow) (about 1937–38), Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College) by Diego Rivera and Girl with Doll (1943, Andrés Blaisten Collection) by Rosa Rolanda, Kahlo’s close friend and fellow artist. Rolanda depicts Kahlo herself as a work of arte popular, in the form of a unibrowed doll tightly clasped in the hands of a wide-eyed little girl.

Painted Miracles / Milagros Pintados

Kahlo collected hundreds of devotional ex-voto paintings, which represent one of her most powerful artistic influences. Tiny images painted on tin, ex-votos express the original owner’s gratitude for miracles and answered prayers. Ex-voto, from the Latin term for devotional offering, is often used interchangeably with retablo, which refers to sacred images placed on altars. Kahlo and her contemporaries redefined ex-votos as arte popular, admiring them for their visionary compositions rather than their religious purpose. The shifting perspectives, combination of standing and floating figures, and metallic support of her painting My Grandparents, My Parents and I (Family Tree) (1936, Museum of Modern Art, New York) recall the ex-voto format. In place of saints, however, Kahlo painted her own ancestors. This section also features another Kahlo painting, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1939, Phoenix Art Museum), and Girl (1925, Andrés Blaisten Collection) a painting by Kahlo’s contemporary Gabriel Fernández Ledesma, which renders the ex-voto as a picture within a picture. Ex-votos from the 19th and 20th centuries are on view, as well as a rare 18th-century example: Peres Maldonado Ex-voto(1777, Davis Museum at Wellesley College), a violent yet beautifully painted work that shows a woman undergoing breast cancer surgery. In 1939, Surrealist André Breton, who had acquired this ex-voto during a visit to Mexico, displayed it alongside paintings by Kahlo in an exhibition in Paris titled Mexique. A letter written by Kahlo, in which she critiques Breton’s curatorial vision, is also on view in this section.

Living Still Lifes / Naturalezas Vivas

Kahlo engaged with the art historical genre of still life, especially in the later stages of her career, but innovated the tradition even as she worked within it. She aggressively filled small-scale compositions with round, vividly colored forms that look like they might tumble out of the picture. She painted fruits and rocks as though they had eyes, skin and feelings, giving them humanlike qualities that are also visible in many works of arte popular. Like the springy Skeletons (about 1940, San Antonio Museum of Art, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Mexican Folk Art Collection) originally made for the Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) holiday, Kahlo’s naturalezas vivas—“living” still lifes—disobey the categories of inanimate and animate, things and beings, dead and living. Three lively and colorful Kahlo paintings are included in this section—Still Life: Pitahayas (1938, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art), Still Life with Parrot and Fruit (1951, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin) and Weeping Coconuts (1951, LACMA)—alongside Cupboard (1947, Andrés Blaisten Collection) by María Izquierdo, Kahlo’s contemporary and a fellow collector of arte popular.

Invented Traditions / Tradiciones Inventadas

Just as Kahlo used paint to create pictures, she used clothing to create her own image. Garments, headdresses and accessories from Mexico’s rural and indigenous communities became her most visible collection of arte popular, worn during international travels and immortalized in photographs. The huipil (rectangular blouse), rebozo (traditional shawl) and regional Tehuana dress were not only critical to Kahlo’s self-fashioning, but also represented broader notions of ideal, “authentic” Mexican femininity. Kahlo made the Tehuana style her signature look—wearing, painting and even gifting the distinctive dresses to people outside of Mexico. The garments in this section include a two-piece Tehuana dress (top and skirt) (1930s–1940s), on view for the first time since it was acquired by the MFA in 2017. Although Kahlo did not wear the dress herself, it was purchased with her help by Jackson Cole Phillips, the original owner of her painting Dos Mujeres.

Graciela Iturbide’s El baño de Frida(Frida’s Bathroom)

A selection of 15 works from El baño de Frida (Frida’s Bathroom), a series by photographer Graciela Iturbide (born 1942), is on view in the Art of the Americas Wing concurrently with Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular. When Kahlo died in 1954, the grief-stricken Rivera took her personal belongings and locked them in her bathroom at the Casa Azul. Fifty years later, the space was finally opened, and Iturbide was commissioned to photograph it. Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico, the first major East Coast exhibition of Iturbide’s work, is on view in the Henry and Lois Foster Gallery through May 12, 2019. The photographs from El baño de Frida (Frida’s Bathroom) will remain on view in the Art of the Americas Wing through June 16, 2019.